Remembering the Ludlow Massacre

Part 3: The Massacre and the Ten Days War

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

By Jack Hood

31 May 2012

The following is the third installment in a four-part series on the Colorado miners’ strike of 1913-1914. The first part was posted May 29; the second part was posted May 30.

On April 19, 1914, Eastern Orthodox Easter for many of the miners, the strikers and their families at the Ludlow tent city were content that the coldest months were behind them. They spent the day picnicking, dancing, singing, and playing baseball. They slept late the next morning.

Early on April 20, the National Guard, led by Major General Patrick Hamrock, coaxed strike leader Louis Tikas out of the camp to discuss the contents of a forged note that claimed strikers had kidnapped a townsperson. When Tikas reached the Guardsmen, soldiers moved with a Gatling gun to Water Tower Hill—a slightly-raised point located some hundreds of yards away from the strikers’ tent city— and opened fire on the tent village below.

Water Tank Hill [Photo: Jozef Kubiš]

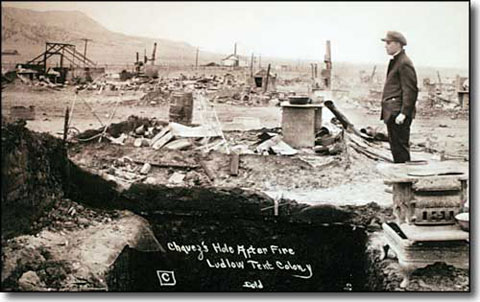

Water Tank Hill [Photo: Jozef Kubiš]Months earlier, strikers had dug a seven-foot deep hole underneath a tent so that children and pregnant women would have a place to hide when agents and guardsmen carried out their random shootings. Under fire again, many women and children ran to hide in the shelter.

National Guard reinforcements arrived within an hour. Other strikers’ tent cities were in communication with Ludlow, but were told by Tikas to stay and defend their camps.

Workers were forced to retreat, and company agents and guardsmen began to set fire to the tents in Ludlow. Fires raged, destroying the city. The remaining inhabitants of the tents began to flee across a field to the East.

Eleven children and two mothers were caught in the cellar beneath a burning tent. Among the dead were Patricia Valdez and four of her children: Elvira, 3 months old; Mary, 7; Eulalia, 8; and Rudolph, 9. Three Petrucci children were killed as well: Frank, 6; Joe, 4; and Lucy, 2. Two Pedregone children also died. Rogerio was six; Cloriva was 4. Fedelina Costa died with her two children, Onafrio, 6; and Lucy, 4. The father, Charles Costa, was also shot in the attack that day. Their bodies were left to rot in the “Death Pit”, as it became known, for days.

Costa gravestone [Photo: Jozef Kubiš]

Costa gravestone [Photo: Jozef Kubiš]Louis Tikas and UMW Secretary James Fyler ran back to the tents to rescue the women and children stuck in the safety bunker. They were captured on the way. Lieutenant Linderfelt promptly broke the butt of his rifle over Tikas’ head, and then shot him three times in the back. Fyler was found with one bullet hole in his head. The two of them were dragged.

For three days the agents and Guardsmen closed off the massacre area and refused admittance to anybody not affiliated with the CFI—even the Red Cross was prevented from entering the camp for 48 hours. The bodies of Tikas and Tyler were displayed on the side of the railroad tracks, where they could serve as warnings for the workers of the area passing through by train. They were only moved when railroad workers objected. “For God’s sake,” they insisted, “they are human souls and deserving of decent burial.”

Ludlow destruction

Ludlow destructionThe events of April 20 would galvanize a movement that over the next 10 days would come to be one of the most militant in American history. Word spread of the massacre, and workers sought revenge.

The response was overwhelming. Railroad workers refused to take troops from Trinidad to Ludlow. In Colorado Springs, 300 miners walked out, armed themselves, and set off for Ludlow. Phone lines were cut. The Denver Cigar Makers Union took a vote and sent five hundred men with weapons to Ludlow and Trinidad. Four hundred women in the United Garment Workers Union volunteered to help the strikers as nurses.

Under the direction of Lieutenant Governor Stephen Fitzgarrald, the National Guard attempted to regroup and raise a new force. Though Gen. Chase and others wanted 600 men, they could only manage a force of 350—far smaller than the strikers’ army of 1,200. Eighty-two of the soldiers ordered to go refused. A newspaper reported that “[t]he men declared they would not engage in the shooting of women and children. They hissed the 350 men who did start and shouted imprecations at them.”

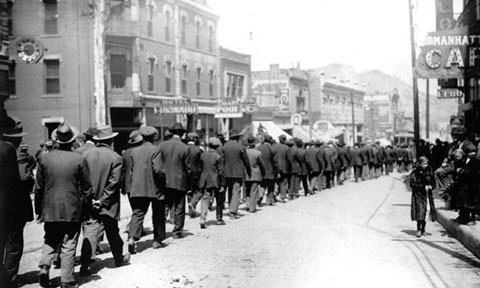

Hundreds of armed miners organized in military groupings and set out to punish the mine thugs. Wielding banners and pickets that advocated worker control of the coalmines, their rallying cries were “burn the bastards out of the state,” and “Remember Ludlow!”

Striking miners

Striking minersOn April 22, after workers had regrouped in the Black Hills and shared their stories with one another, the miners attacked the Empire Mine near Aguilar. Ironically, mine owners and their families retreated into the mine pit in an act of desperation. Miners, unlike their counterparts, released the women and children, and did not fire upon the trapped mine owners. They were released after two days when the strikers moved on to attack another mine.

Subsequently, miners moved out to attack Delagua, Tabasco, Berwind, Rouse, Primrose, Broadheds, and several other mining operations. On April 23, the company agents and National Guard began a counter attack, hitting Aguilar and Ludlow. On the 25th, they struck the Chandler mine facility, which was held by workers.

Shortly after the massacre in Ludlow, 5,000 demonstrated in Denver, asking the Governor to resign over the treatment of the workers. Thousands more attended funeral processions through Trinidad. On April 27, Louis Tikas was buried as workers attacked and took over four more mines, including the Walsen Mine. Gen. Chase was forced to send 100 troops into Boulder County, as workers much farther north joined in the mine attacks. Days later, the 11 children and 2 women whose remains were found charred in the Death Pit were carried through Trinidad in a convoy of tiny caskets.

Tikas' funeral

Tikas' funeralOn April 28, at the request of Gov. Ammons, President Wilson sent in 1,000 troops from the US Cavalry to Las Animas and Huerfano counties. There were fears that the insurrection could spread to other states, including Michigan, where thousands of copper miners were also on strike.

“With the deadliest weapons of civilization in the hands of savage-minded men, there can be no telling to what lengths the war will go in Colorado unless it is quelled by force,” the New York Times wrote. “The President should turn his attention from Mexico long enough to take stern measures in Colorado.”

But before the US Cavalry arrived, a large group of strikers marched north to Walsenburg, where they set up a perimeter and took over a hill overlooking the town. They fought off a three-day attack from company thugs, and attacked the Forbes mining operation. On April 29, they captured four scabs and guards, whom they later released. Four strikers and ten company thugs were killed in the battle at Walsenburg.

With federal troops in the area to get the mines running again, the strike faded out. Finally, on December 10, 1914, the UMW abandoned the strike, and the strikers were left without work, without homes. The UMW attempted to halt the mine takeovers and defuse the situation.

Sixty-six strikers and family members were killed. Not a single company thug or National Guardsman spent a night in jail.

Ludlow strikers

Ludlow strikersFueled by public outcry in response to the Ludlow Massacre, the Commission on Industrial Relations (also known as the Walsh Commission) subpoenaed John D. Rockefeller, Jr. to respond to claims that his company was responsible for the violence in southern Colorado. Rockefeller blamed outside organizers for the strike.

Although the findings of the Walsh Commission in response to Rockefeller’s testimony brought national attention to the actions of CFI and the National Guard in southern Colorado, ultimately no government action was taken against Rockefeller or those directly responsible for the Ludlow Massacre.

The historical impact of the Walsh Commission (which published its final reports in 1916) is subject to much debate among historians, but the conclusions released on the subject of poor industrial and agricultural working conditions played a part in the Democratic Party’s turn towards welfare capitalism over the subsequent decades.

In fact, the commission itself put forward the position that closer coordination would be needed between labor and big business in order to subdue the threat of social upheaval:

“Where (labor) organization is lacking, dangerous discontent is found on every hand; low wages and long hours prevail; exploitation in every direction is practiced; the people become sullen, have no regard for law and government, and are, in reality, a latent volcano, as dangerous to society as are the volcanoes of nature to the landscape surrounding them.”

Follow the WSWS