Prelude to the Emancipation Proclamation

150 years since the Battle of Antietam

By Tom Mackaman

17 September 2012

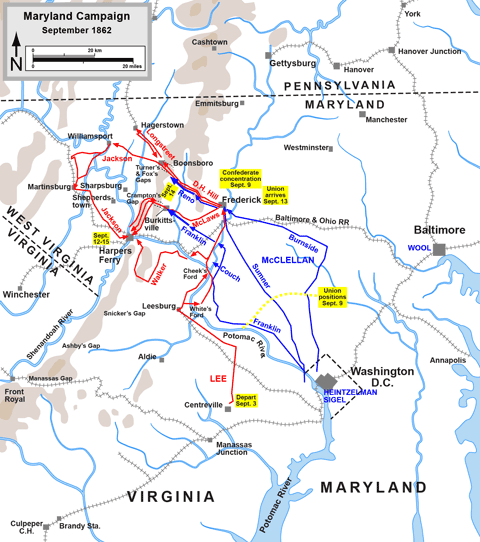

One hundred fifty years ago, on September 17, 1862, in the second year of the American Civil War, the armies of the Union and the Confederacy met by Antietam Creek, near Sharpsburg, Maryland. The battle that ensued remains the bloodiest single day for US troops in American military history. In one day of fighting there were some 23,000 casualties, with nearly 3,700 soldiers killed.

Yet the significance of the Battle of Antietam goes far beyond its casualty toll. The strategic union victory—resulting in the expulsion of General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia from Maryland and the North—had immense ramifications. Most importantly, it set the stage for President Abraham Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, the executive order that led to the freeing of the slaves.

Lincoln abhorred slavery. “If slavery is not wrong, nothing is wrong,” he had said. But until 1862 he had articulated a position that would have restored the Union to its state prior to the war, with slavery permitted where it already existed but blocked from expanding to new territories.

The first year of the Civil War had changed Lincoln’s thinking. Southern success and Northern futility in the field had convinced him that it was not possible to achieve the aim of preserving the Union without aiming a death blow against the entire social order in the South. Slavery had to be destroyed.

“This government cannot much longer play a game in which it stakes all, and its enemies stake nothing,” he said. Emancipation was “a military necessity, absolutely essential to the preservation of the Union. We must free the slaves or ourselves be subdued.”

This effectively transformed the war into a social transformation—the second American revolution.

In July 1862, Lincoln told his cabinet, to their astonishment, that he intended to issue an executive order of emancipation. Frustrated with the lack of support for even modest anti-slavery measures from the slaveholding border states still in the Union, Lincoln had determined to bypass Congress by invoking his military power as commander-in-chief. But on the suggestion of his secretary of state, William Seward, Lincoln agreed to wait for some success on the battlefield before making public the proclamation. That success turned out to be the Battle of Antietam.

The leaders of the South were making their own calculations. If the Army of Northern Virginia could follow up its successes in the late summer of 1862 with an invasion of the North—simultaneous invasions of Kentucky and Union-held parts of Mississippi were to be launched from the western theater— it would take the burden off the ravaged Virginia countryside, deliver a blow to Northern morale and, most important, make more probable diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy by Great Britain and France, and perhaps their intervention in the war.

The leaders of the South were making their own calculations. If the Army of Northern Virginia could follow up its successes in the late summer of 1862 with an invasion of the North—simultaneous invasions of Kentucky and Union-held parts of Mississippi were to be launched from the western theater— it would take the burden off the ravaged Virginia countryside, deliver a blow to Northern morale and, most important, make more probable diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy by Great Britain and France, and perhaps their intervention in the war.

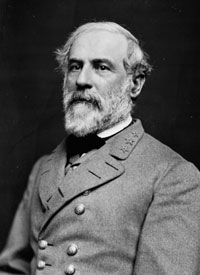

Robert E. Lee

Robert E. LeeIt was with these goals in mind that Robert E. Lee, fresh from his victory at the Second Battle of Bull Run on August 30, 1862, took the Confederate Army across the Potomac.

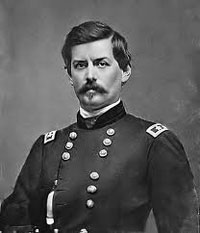

There was no doubting the numerical and material superiority of the Union army. But Lee had taken the measure of his opponent, General George McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac. Experience had taught that McClellan would not engage his entire army in a battle, that he would not concentrate his forces for an attack, and that he would not pursue the Confederates even when he had achieved a tactical victory.

For a year, McClellan had resisted Lincoln’s entreaties to press the attack in Virginia. From his telegrams, diaries and letters, historians have found that McClellan overestimated two- or three-fold the size of the Confederate forces he faced. Objects that McClellan thought to be massive cannons turned out to be logs. The Army of the Potomac, for one reason or another, was never ready to attack. “All Quiet on the Potomac,” the northern press mocked.

George McClellan

George McClellanBut McClellan was not a fool. From an elite Philadelphia family, McClellan was a master organizer—a skill much appreciated by Lincoln after “the boy general” was elevated to commander in the wake of the humiliating Union defeat in the First Battle of Bull Run at the war’s beginning. He was also, prior to Antietam, much loved by the rank-and-file soldiers of the Army of the Potomac. These factors prevented Lincoln from dumping McClellan. “I will hold his horse,” Lincoln told an exasperated secretary, “if he will bring us success.”

McClellan’s blunders and unwillingness to commit to a fight grew out of his political position. He did not oppose slavery, and he neither sought nor desired a total defeat of the South. A northern Democrat, McClellan hoped to maneuver the Army of the Potomac to confront Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, in such a way as to force a negotiated settlement and a return to the status quo ante: the restoration of the southern states to the Union with slavery intact.

On September 3, Lee took his army of 55,000 into Maryland and divided them three ways in order, in part, to confuse the Union generals and, in part, with the hope that the presence of the Confederate army would rouse Maryland to the Southern cause. In this Lee was disappointed. Where his army marched, Marylanders closed their doors and windows. They cheered the advancing Union army.

By the morning of September 16, McClellan was facing Lee at Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg. Though the Union force was three times larger than Lee’s 18,000 soldiers, McClellan determined not to attack, estimating that 100,000 Confederates lay in wait. The delay allowed the Confederates to regroup, with generals George Longstreet and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson returning and bringing the Union advantage down to a 2-1 ratio.

Heavy fighting began before dawn on September 17. In its first phase, the battle unfolded in and around a farm now known as “the Cornfield.” The field changed hands again and again—15 times according to one estimate—with neither side able to achieve an advantage. Hand-to-hand fighting unfolded amongst the maize, while from both sides artillery batteries, canister fire and rifle volleys strafed the combatants. The 12th Massachusetts Infantry and the Louisiana “Tiger” Brigade each lost about two-thirds of their soldiers, dead and wounded. By noon there were a total of 13,000 casualties.

"The Cornfield"

"The Cornfield"Union General Joseph Hooker described the aftermath. “[E]very stalk of corn in the northern and greater part of the field was cut as closely as could have been done with a knife, and the slain lay in rows precisely as they had stood in their ranks a few moments before.”

In the late morning, the focus of the fighting shifted to an area in the middle of Lee’s line of defense that took the name “The Sunken Road” or “Bloody Lane.” There, about 2,500 Confederates had found a good defensive position in the depression of a road near the top of a small hill. The position held for two hours until the 64th New York pushed through and turned their fire on the now-trapped Confederate defenders.

However, under heavy artillery fire, the Union soldiers were unable to take advantage of the initial break. McClellan decided not to send forward upwards of 20,000 additional soldiers waiting nearby who might have broken the Confederate defense.

Aftermath of the battle

Aftermath of the battleThe final stage of the battle took place in the afternoon on Lee’s right flank. Thousands of Union soldiers died in an attempt to dislodge well-placed Confederate defenders on a bridge crossing Antietam Creek. They ultimately broke through, but were then repulsed by recently arrived Confederate reinforcements under General A.P. Hill, and once again McClellan determined not to commit reserve soldiers to the attack.

By early evening the battle was over. There were more Union casualties than Confederate—about 14,500 versus about 12,000—but Lee had lost a greater share of his much smaller army, nearly one-third dead or wounded after one day of fighting. About one third of McClellan’s army had not even engaged in the battle. Each side lost three generals.

Pinned with his back against the Potomac, Lee waited for the expected attack from the much larger and better-equipped Union force. It never came. McClellan allowed the Army of Northern Virginia to slip away, unmolested, back over the Potomac. For the next month McClellan refused requests from Washington that he pursue Lee into Virginia.

Finally, on November 7, 1862, Lincoln removed McClellan from command. Precisely two years later McClellan would confront Lincoln as the Democratic Party candidate for the presidency, running on a platform that would have led to the recognition of Southern independence and the perpetuation of slavery. In that election year, 1864, the electorate repudiated McClellan and his party, Lincoln was reelected and a Radical Republican Congress was put in power that would push through the Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, abolishing slavery.

Lincoln meeting McClellan at Antietam

Lincoln meeting McClellan at AntietamIn the shorter term, the tactical victory in Maryland allowed Lincoln to make public his Emancipation Proclamation, which made possible not only the Thirteenth Amendment but also Union victory in the war. Lincoln announced the Proclamation five days after Antietam, delaying the announcement until he was certain that the battle had, in fact, been a Union victory.

The executive order would go into effect January 1, 1863 and would free all slaves in rebel territory. It did not—nor could it as a military order—free slaves in the slaveholding Union states (Missouri, Kentucky and Maryland) or in former rebel states under Union political administration. This led some observers to ridicule Lincoln for “freeing the slaves where he couldn’t and leaving them enslaved where he could.”

Yet the significance of the Emancipation Proclamation was not lost on most contemporary observers. The war to preserve the Union was now the war to destroy slavery.

The northern Democratic press launched vicious, race-baiting attacks on Lincoln. The Southern elite was apoplectic. They knew well that the Proclamation was an invitation to slave revolt.

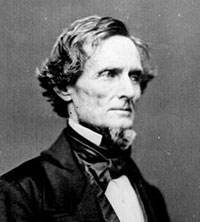

Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, called it “the most execrable measure in the history of guilty man.” Still camped at Antietam, McClellan was furious. “I cannot make up my mind to fight for such an accursed doctrine as that of servile insurrection,” wrote the top Union general.

Jefferson Davis

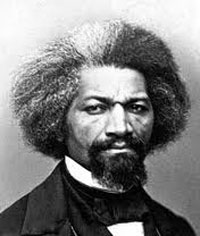

Jefferson DavisMany in the North welcomed the Proclamation, especially the abolitionists who had been pressing Lincoln to attack “the Slave Power” at its root. “To fight against slaveholders, without fighting against slavery, is but a half-hearted business,” Frederick Douglass had told Lincoln. “War for the destruction of liberty must be met with war for the destruction of slavery.”

In the latter years of the war this sentiment mounted, but in the November, 1862 federal elections the Republican Party suffered losses, as Lincoln had anticipated.

Frederick Douglass

Frederick DouglassThe Battle of Antietam and the Emancipation Proclamation removed the likelihood of British or French recognition of the South. This was not due to British ruling class opposition to slavery. On the contrary, the British elite, which controlled the lion’s share of the South’s cotton trade, had hoped for a Southern victory.

But British ruling circles had to contend with the hatred of the working class for slavery, which began to coalesce into a mass political movement after the Proclamation. “The Lancashire operatives [are the only] class which as a class continues actively inimical to us,” a Southern spy operating in England wrote.

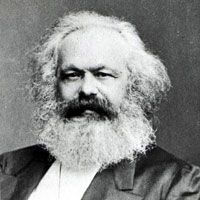

Karl Marx

Karl MarxThis was so even though the Union blockade denied their mills supplies of Southern cotton. “Even in the face of economic ruin,” writes historian Allen Guelzo, “British workers could not be persuaded to make cause with Southern slaveholding; and between January and March 1863, a series of mass demonstrations in Manchester and London cheered Lincoln and his Proclamation.”

Karl Marx, who followed closely the progress of the Civil War from London, summed up Antietam in its immediate aftermath. The battle, he said, “has decided the fate of the American Civil War. As the American War of Independence initiated a new era of ascendancy for the middle class, so the American anti-slavery struggle will do for the working masses.”

Follow the WSWS