This week in history: December 3-9

3 December 2012

This Week in History provides brief synopses of important historical events whose anniversaries fall this week.

25 Years Ago | 50 Years Ago | 75 Years Ago | 100 Years Ago

25 years ago: Beijing protest against murder of student

Hu Yaobang

Hu YaobangA thousand students marched in Beijing on December 8, 1987, protesting the murder of fellow student three days earlier. This was the first public demonstration by university students in Beijing since the previous winter when nationwide protests forced the ouster of Communist Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang. Subsequently, all public protests were banned by the state.

Zang Wei, 19, a student of business management at the University of International Business and Economics, who was stabbed multiple times by a thug. Students said that he could have survived the stab wounds if he was treated immediately by medical personnel at both the university clinic and the Sino-Japanese Hospital, the best-equipped facility in Beijing, where he was sent later.

Students participating in the march said. “We are protesting for our dead schoolmate,” and “We are protesting against the bureaucracy.” Several students explained that they were unsuccessful in their attempts to discuss the stabbing with university officials, so they decided to hold the march.

Police became more brutal to the marchers as they got closer to Beijing’s central thoroughfare, Changan Boulevard. Students described to media how police assaulted them. At the end of the eight-mile march, the crowd had grown to several thousand and thronged inside the gates of the Ministry of Foreign Economic Relations and Trade, the parent institution of the university. When officials from the university attempted to assuage the crowd with platitudes, the response from the assembled march was jeers and catcalls. Students shouted “bureaucratic jargon and rubbish,” then issued a list of demands, including reorganization of school administration and disciplining “inept” hospital staff and security guards.

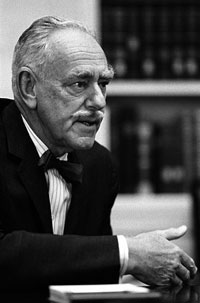

50 years ago: Acheson belittles Britain in West Point speech

Dean Acheson

Dean AchesonOn December 5, 1962, former US Secretary of State Dean Acheson delivered a speech to the Army Academy at West Point that singled out the United Kingdom for sharp criticism. Acheson said Britain had “about played out” its attempt to assume an independent role from the US in world affairs—an apparent reference to London’s humiliation in the Suez crisis of 1956—and further that “Great Britain has lost an empire and has not yet found a role.” He also criticized Britain’s modest attempts to mediate between the US and the Soviet Union.

The reaction to Acheson’s speech in British ruling circles was one of “anguish,” according to the Times of London. While the Tory administration of Harold MacMillan quickly pointed out that Acheson was retired, “the British, however, recognize that some of the comments… do reflect the [Kennedy] Administration’s views,” according to the New York Times. MacMillan felt compelled to make public a letter suggesting that in underestimating Britain Acheson—then a private citizen— was repeating an error “made by a lot of people in the course of the last 400 years, including Philip of Spain, Louis XIV, Napoleon, the Kaiser, and Hitler.”

The speech was taken as a blow to the UK’s international standing. According to the New York Times, British “government sources said they feared Mr. Acheson’s discounting of Britain’s present status might add to the difficulties in the Government’s convincing France and other members of the European Economic Community of her value as a member.”

Indeed, in Europe Britain was also marginalized. France and West Germany moved the same week to block its bid to join the six-nation European free trade consortium called the Common Market, or EEC. On December 5 West Germany, France, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxemburg unanimously ruled that Britain would have to immediately conform to Common Market agricultural subsidies and tariff polices. This threatened the privileged tariff policies with Britain’s former colonies in its Commonwealth organization and its existing trade agreements with certain European countries, including Sweden.

75 years ago: Japanese forces demand surrender of Nanking

Chinese dead in Nanking

Chinese dead in NankingAt noon December 9, 1937 Japanese aircraft dropped leaflets over the capital of China’s Jiangsu province, Nanking, demanding an unconditional surrender of the city and the remaining Chinese military forces within. The ultimatum was signed by General Matsui, the commander in chief of Japanese troops on the Shanghai-Nanking front, and was addressed to General Tang Shengzhi of the Nanking garrison.

Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek left Tang in charge of defending the city against the Japanese attack after he and his entourage fled to Wuhan. Nanking had been designated the Chinese capital after the fall of Shanghai to Japanese forces earlier in the year.

The London Times printed verbatim the demand; “Unless the Chinese troops in Nanking surrender by noon on December 10 the horrors of the war will be let loose on Nanking. Nanking abounds in historic monuments and beauty spots; it is indeed the keystone of Oriental civilisation.” On the same day that the military ultimatum was made, Japanese forces occupied points near the Yangtze River in order to cut off the escape routes from Nanking.

Between 200,000 and 300,000 Chinese civilians were massacred when the city fell two weeks later.

The London Times noted a telegram received by the Chinese Embassy in the British capital conveying the magnitude of the situation: “Desperate fighting is proceeding in the suburbs of Nanking. The Chinese are making a determined stand around the capital and preparations have been completed for possible street fighting within the city.” Chinese troops razed buildings in the path of the Japanese advance, in order to remove all prospective cover for the advancing columns. The whole district of Hsiakuan, containing the capital’s waterfront and railway station, were sacrificed in this manner. Reuters reported that the defensive boom across the Yangtze River near to Nanking had been broken and Japanese destroyers were steaming up the river towards the Jiangsu province city.

100 years ago: Germany prepares for European conflagration

German Imperial War Council, 1914

German Imperial War Council, 1914On December 8, 1912, the military and civilian leaders of Germany met in Berlin to hold an informal conference dubbed the German Imperial War Council. The meeting, which took place in the context of the ongoing Balkan War, was centrally concerned with the possibility of a conflict with Serbia and Russia.

It was precipitated, however, by indications of closer Anglo-French ties. Prior to the conference, Lord Haldane, the British War Minister, told the German ambassador in London that Britain would unconditionally support France in the event of a European conflagration. The alliance between Britain and France, known as the Entente Cordiale, had been strengthened in November by an exchange of notes between British Foreign Secretary Edward Grey and the French ambassador to Britain, assuring each other of joint action in the event of war.

The meeting was reportedly convened as a result of the Kaiser Wilhelm II’s anger at the growing Anglo-French alliance, which appeared to be directed against an expansion of German influence in Europe.

Wilhelm II denounced Britain’s policy in Europe as “idiocy”, and called for an Austro-Hungarian attack on Serbia. He commented that if in the event of an Austro-Hungarian attack on Serbia, “Russia supports the Serbs, which she evidently does…then war would be unavoidable for us, too.” Differences emerged between the Navy, and the army at the conference. General von Moltke, head of the army, called for immediate attack, stating, “A war is unavoidable and the sooner the better.” Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz, head of the Navy, disagreed, calling for the “postponement of the great fight for one and a half years”, on the grounds that the German Navy was not equipped to fight a continental war that would likely involve intervention. During the course of the conference Tirpitz’s position won the support of the Kaiser, and Moltke relented.

Follow the WSWS