Exhibition of Russian-Soviet artist Vladimir Tatlin in Basel—Part 6

An interview with Anna Szech, art historian at the Museum Tinguely

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

By Sybille Fuchs and Marianne Arens

30 June 2012

This is the sixth and final article in a series devoted to an exhibition at the Museum Tinguely in Basel, Switzerland of works by Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953), one of the most important artists of the Russian and Soviet avant-garde. Part 1 was posted June 19; Part 2, June 20; Part 3, June 21; Part 4 June 25 and Part 5 June 28.

Anna Szech

Anna SzechAnna Szech is an art historian born and raised in St. Petersburg, Russia. She studied in Hamburg, Germany and now works as a researcher at the Museum Tinguely in Basel, Switzerland. Her working relations with lending museums and institutions as well as art experts in Russia contributed significantly to the mounting of the current Vladimir Tatlin exhibition. She spoke to the WSWS about the enthusiasm with which her generation has greeted the re-emergence of Russian-Soviet avant-garde art in museums.

WSWS: How do you assess Vladimir Tatlin’s importance for Russian and European art?

Anna Szech: The period from 1905 to about 1920 is a time when Russians not only made an important contribution to European art, they were also influential and played a leading role in the promotion of this art. Western European art has been very much present in Russia since the Middle Ages. Russia also underwent its own distinct artistic development that unquestionably compares to that of Europe.

The origins of this development lie in Byzantine art. Religious icons strongly influenced the selection of themes for artistic imagery right into the 18th century. Afterward, the Russian tsar, Peter the Great, wanted to copy everything—painting, still life, architecture—from the West. Actually, there are hardly any gradual transitions between the stages of artistic development in Russia. Each stage culminates in a sharp break. Initially we have icons, icons, icons—and then, suddenly, gala portraits.

The radical change in Tatlin’s period was extremely important for the whole of European culture. It continues until the death of Lenin in early 1924, when we mark a decisive rupture.

Lenin was a very well-educated man. He spoke, as far as I know, six languages and was certainly not narrow-minded. His view was: “If somebody has to teach the people art, then it must be the artists themselves”.

Lenin’s death in 1924 is followed by a collapse of the early Soviet Union’s cultural upsurge. How did the artists respond? It was an ambivalent reaction. Many intellectuals saw where the change in the Soviet Union was leading. Tatlin was closely associated with [poet Vladimir] Mayakovsky, who committed suicide in 1930. Tatlin arranged his funeral.

Many artists didn’t survive Stalinism, which is a terrible tragedy. [Critics] Nicolai Punin and Aleksandr Voronsky didn’t survive it. Others fled. Some remained because they believed they’d still be able to accomplish their artistic goals. That was what Tatlin thought.

At the beginning of the 1930s, he was still celebrated and accorded an exhibition [1932]. He received several awards from Stalin and was honoured as “merited artist of the people”. He fell from grace virtually overnight.

WSWS: Tatlin’s ideas about the duties of the artist were certainly incompatible with the role prescribed to artists by the Stalinist bureaucracy’s doctrine of “socialist realism”. He always strove to make an impact, but as an artist, not a propagandist. In the artistic debates of the early 1920s, he also rejected the new “scaffold art”, constructivism, as a purely aesthetic principle.

AS: Regarding this, there is a wonderful poster created by Tatlin himself, “Down with Tatlinism”. He had no intention of founding a school. He was a brilliant lecturer and had many students and pupils. But he spurned all the “isms”. He already wanted to overcome them with his counter-reliefs.

There was sharp rivalry between Kazimir Malevich and Tatlin, following the avant-garde 0.10 exhibition in the winter of 1915-16, in which both artists featured their works. A group of followers formed around Tatlin. But he didn’t really want this to happen.

It is fascinating to take stock of Tatlin’s oeuvre: the paintings, the counter-reliefs from 1914 to 1916, the “Tower”, the “Letatlin” [flying apparatus], the theatre works and the paintings again. Only his engagement with the theatre shows any continuity. This begins with his work on the play Tsar Maksemyan [Maximilian] and His Disobedient Son Adolfa [1911] and [Wagner’s] The Flying Dutchman, and he is again working mainly for the theatre at the end of his life.

However, we don’t know what Tatlin would have done if he hadn’t had to contend with the tyranny of Stalinism. I’m always arguing with my Swiss colleagues about this, but I think he really was in a difficult predicament. I think he wouldn’t have confined himself to theatre work in his later years if he’d been allowed to do other things. Had the political situation in Russia been different, perhaps he might have been able to make a further remarkable artistic development.

WSWS: It was a tragedy comparable with the eradication of modern art in Germany under the Nazis. But Tatlin’s late paintings should by no means be underestimated.

AS: Yes, you know what? We actually have three of Tatlin’s late works in the exhibition. I say “actually” because ... You know the wonderful nude study recorded in the Russian State Archive of Literature and Art (RGALI), the female nude in front of the floral curtain? Well, there’s a still life from Tatlin’s late years on the back of it.

Anna Szech in front of Vladimir Tatlin, Lying nude, 1912, RGALI Russia State Archive for Literature and Art, Moscow (on the back of this canvas there is a late still life by Tatlin)

Anna Szech in front of Vladimir Tatlin, Lying nude, 1912, RGALI Russia State Archive for Literature and Art, Moscow (on the back of this canvas there is a late still life by Tatlin) The curator of the RGALI told us an amazing story. They keep documents, posters, letters and photographs in the archives, and they also have these three paintings. One wonders how they came to possess them.

In the 1950s, they literally found them in the garbage.

You get rid of your trash in a particular way in Russia: it’s collected in huge trash containers in the back courtyards and taken away once a week. And in 1953 or 1954 (anyway, after Tatlin’s death), employees of the RGALI received a call from an elderly lady who told them: “I’ve just taken out my rubbish, and I saw several paintings propped against the garbage container. Maybe one of you would like to drop around”.

Stalin died in 1953 and the situation was still very dangerous. They drove to the place and brought the paintings back to the archive, where they discovered they were by Tatlin. Toward the end he was living in very impoverished circumstances and used the backs of pictures as canvases for new works.

The staff of the RGALI still tell of how they often get into a double bind when they receive requests from two different institutions for one of the two different paintings, because in reality there’s only one canvas that has been painted on both sides.

But our exhibition only relates to Tatlin’s late work in passing. Nevertheless, these paintings are indeed quite different, the range of colours is very subdued, withdrawn and intended more for private viewing. It’s very sad to compare the late paintings with his early works, where he is still very energetic and courageous. In his younger days, he’s not afraid to make bold brush stokes or jab the board with a piece of iron. But in his late works he is very tender.

WSWS: Why do you think Tatlin did not capitulate to Stalin and the dictates of the cultural bureaucracy, the demand for “socialist realism”?

AS: Many artists and writers had to repudiate their earlier work and admit it was a mistake. But Tatlin was one of the very few who said they would not renounce their work. Unfortunately, we haven’t been able to find a written record of such a statement on Tatlin’s part, but it is passed on that he did hold this position. He is commonly believed to have said: “The experiences of a man or an artist are his true riches”.

WSWS: How was it possible for Tatlin’s works to survive in the Soviet Union?

AS: The example of the “Corner counter-relief” helps explain this. It appeared quite suddenly; it was recovered, despite being thought “lost”. We don’t know whether there were explicit orders to destroy his works. However, they were probably hidden by fellow artists who had worked with him.

So the model of Tatlin’s tower is still not officially regarded as being lost. It’s still registered in the books of the museum. Maybe it still exists somewhere disassembled in its component parts.

Many works survived in the provinces, which can only be attributed to the artistic appreciation and professional devotion of museum staffs.

WSWS: In his opening remarks, Mr. Wetzel said that Tatlin is greatly esteemed in Russia. Does this only apply to museum devotees or do you feel that broader sections of the population is interested in him? Is there such a thing as a Tatlin renaissance in Russia?

AS: I am firmly convinced that people who are no longer quite so young know of Tatlin; he is more or less a famous name for the older generation. The galleries that contributed Tatlin’s works to this exhibition said: “You realise, of course, that (without Tatlin’s pictures) our halls will be empty”. But very young Russians in their twenties often know nothing about him.

Those who know Tatlin know him very well. Tatlin offers such profound works: the paintings, the counter-reliefs, the theatre pieces, and they know he is the creator of the Letatlin and the Monument to the Third International.

Tatlin has become very popular in the West. An astounding number of people were at yesterday’s opening. That’s because Tatlin is a real attraction. We were very pleased about it.

Apart from the appreciation shown by museum staff and some museum visitors, attitudes to Tatlin and the avant-garde are rather reserved in Russia. The Rossiya Hotel in Moscow was recently demolished. A proposal was made to have Tatlin’s tower erected in the vacant space, but this was rejected. And if you Google the name “Tatlin”, you’ll only find a few short newspaper articles. In the last fifteen years, only one doctoral dissertation has been written, about five years ago, dealing with Tatlin’s late work.

WSWS: So how do you explain the great interest in the exhibition here in Basel? Has Tatlin suddenly come back into vogue?

AS: That’s certainly the case. Today the approach to artistic creativity proposed by Tatlin is being reconsidered. People are interested in the historical and political background to his work. He stated his opinion about October 1917 so clearly, declaring himself on the side of the new society. A revival of interest in such an attitude is obviously underway today.

Tatlin very much regretted that his tower was not actually built. It was completely impractical at the time, but Tatlin himself was not well understood. The idea of erecting a glass building was ignored. The tower was supposed to contain a number of rotating buildings, and the upper half was to turn once a day in order to ensure that the press remained vigilant.

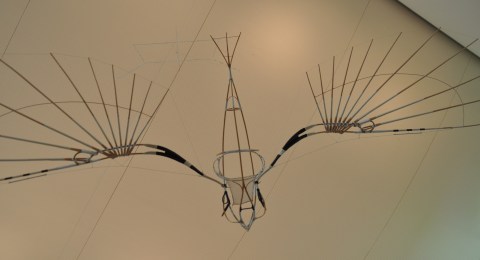

Vladimir Tatlin, Letatlin [1929-1932], reconstruction of George Athanassopoulos, photo WSWS

Vladimir Tatlin, Letatlin [1929-1932], reconstruction of George Athanassopoulos, photo WSWS Tatlin sometimes made contradictory statements about his works, and so it was with the Letatlin. At one time, he declares the Letatlin is clearly meant to fly and will fly too. Then you find him saying it’s a purely aesthetic work.

But artists are not in the business of explaining their work. They’re there to create beautiful, ingenious things.

Concluded

Follow the WSWS