Exhibition of Russian-Soviet artist Vladimir Tatlin in Basel—Part 4

Interview with Dmitrii Dimakov, expert on Tatlin’s work

Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

By Sybille Fuchs and Marianne Arens

25 June 2012

This is the fourth of six articles devoted to an exhibition at the Museum Tinguely in Basel, Switzerland of works by Vladimir Tatlin (1885-1953), one of the most important artists of the Russian and Soviet avant-garde. Part 1 was posted June 19; Part 2, June 20; and Part 3, June 21.

Dmitrii Dimakov

Dmitrii Dimakov Dmitrii Dimakov teaches in Penza in southeastern Russia, at the art school where Vladimir Tatlin completed his training in calligraphy and as a graphics teacher in 1910. He and his team not only built one of the two models of Tatlin’s famed Monument to the Third International for the Basel exhibition, but also reconstructed some of the artist’s counter-reliefs. Dimakov is considered one of the leading experts on Tatlin’s work.

We spoke to Dimakov in Basel about Tatlin and his own work.

WSWS: How do you explain the legendary status of the tower—given the fact that Tatlin himself was relatively unknown to a wider audience for a long time and his tower was never built?

Dmitrii Dimakov: Tatlin’s tower emerged in the 1920s. It was one of the first works intended to symbolize the new revolutionary Russia. Its other name was “Monument to the great Russian Revolution”. It was anything but a memorial to the dead, rather a monument that celebrates the vibrancy of life.

Tatlin’s name was perhaps not so well known because he was not the sole inventor of the tower. It was a collective work. Tatlin was a colourful, flamboyant artist. He had the ideas, and played the leading role in the hierarchy of a collective where he provided the basic concepts. He was surrounded by a close circle of students and staff, and a second group of students who helped execute his plans.

This form of collective work corresponded well to the new idea of the artist and how the training and the creation of art under new conditions should be carried out. Tatlin was a prominent protagonist of this new method.

WSWS: What was the fate of the original models?

DD: Regarding the fate of the originals, it is correct that Tatlin created two models. The first in November 1920, and a second in 1925 for the Paris World Exhibition. The first model was built in Petrograd, then taken to Moscow and exhibited in the Union House, where it remained for several years. It was later moved to the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow.

The second returned from Paris to Russia and was taken to Petrograd to the Russian Museum. During the Second World War it was destroyed, probably burned as firewood. Perhaps it helped save the lives of a few people.

As for the model at the Tretyakov Gallery, it was deposited in a Moscow church along with the whole sculpture department to protect it from bombing. After the war, when the sculptures were brought back to the gallery, the tower model was no longer among the exhibits. It is believed to have been destroyed, but that is not documented. The gallery continues to include it as a possession in its catalogue.

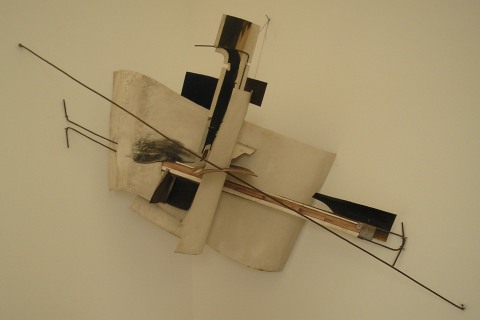

Dimakov’s team reconstructed Tatlin's counter-relief

Dimakov’s team reconstructed Tatlin's counter-relief WSWS: How did you arrive at the decision to reconstruct a model of Tatlin’s tower?

DD: My own interest in reconstructing was aroused for the first time in 1978. At that time there was a fierce debate over the reconstruction built by T.M. Shapiro, Tatlin’s student who had helped build one of the original models. A gathering of art historians and architects who expected to see the reconstruction of Tatlin’s model were disappointed with Shapiro’s end result.

Shapiro regarded himself as co-author of the original model and therefore thought he had a right to make changes to its form. It was certainly possible to recognize Tatlin’s tower in his reconstruction, but at the same time it was clearly not “Tatlin’s Tower”.

The accompanying exhibition, the historical footage, photographs, books, journals—this was all much more interesting than Shapiro’s reconstruction.

At that time I had studied architecture and was most interested in all that. This spurred my obsession to rebuild the model. I started to develop the construction from a simple wire spiral.

In 1985, when I began to teach at the Penza Art College, we were the only ones to celebrate the 100th anniversary of Tatlin’s birth. We began with a relief-like reconstruction of the tower.

In 1989 the first international symposium dedicated to Tatlin took place in Düsseldorf, Germany. This was a powerful impetus. A number of speeches were devoted to the reconstruction. Everyone spoke about the difficulties involved and how hard it was even for architects to recognise the problems in advance.

Tatlin’s tower had been reconstructed in 1968 for the Stockholm exhibition devoted to him. [1] I first saw a model, however, in Moscow at the 1980 exhibition entitled “Moscow-Paris/Paris-Moscow”.

Following the upheavals of the late 1980s, one began to feel much more free to express oneself. Initial articles about Tatlin started to appear and suddenly there was a wave of interest in studying him. In 1990 I started to put together a team and commenced looking for a suitable workshop.

In 1992 we created a smaller, two-meter-high model, with which we were basically satisfied. All the details were in place and seemed to be correct viewed from the different sides when we compared our model to the pictures that had been made of the original tower.

Dmitrii Dimakov and his colleague, Igor Fedotov, in front of their reconstructed model of Tatlin’s Tower

Dmitrii Dimakov and his colleague, Igor Fedotov, in front of their reconstructed model of Tatlin’s Tower Then we expanded the model up to a total of 6.4 metres [21 feet] i.e., 5 metres above the base. Only then did we insert the base, which has its own plastic function. We regarded our work very much as a kind of archaeological dig: we had to explore every detail, including Tatlin’s motives, and why such and such was the shape it was, and not otherwise.

WSWS: When the “tower” emerged in the 1920s, it unleashed fierce debates amongst artists and in the new workers government, especially in the Department of Fine Arts of the People’s Commissariat of Education. Can you say something about this?

DD: The discussion centred on how to assess the principle of construction. The visual artists and painters took the initiative and insisted—against Tatlin’s views—that the construction is not the defining element of art, but only one element of the composition of a piece of art. For them, the constructivist elements were more like a blank surface to be worked upon.

Tatlin went beyond that. The only work which he believed could rightfully be attributed to constructivism was his “tower”.

That is why Tatlin’s is called the “father of constructivism”. In fact those who described themselves as constructivists in the Soviet Union had very different notions to those of Tatlin.

WSWS: What is the significance of this debate in Russia today, if it has any?

DD: Tatlin had—and still has—no direct successor. Rather, he is much more an undisclosed figure. Contemporary artists do not understand him, probably because they want to achieve something “finer”, purely aesthetic with their art.

WSWS: Tatlin was linked to the revolution. This is precisely what most artists reject today?

DD: Exactly, that’s a correct way to put it. Nobody is really interested in the concepts of Tatlin today. The essence of things, the study of how things affect people, these questions remain unanswered. Perhaps only the very young are once again showing interest in such issues.

WSWS: Tatlin’s tower is at the centre of the “Building the Revolution” exhibition, currently at the Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin. Architects in the early years of the Soviet Union evidently focused their interest on him and his ideas. But the buildings that still exist from this period are in poor condition.

DD: Yes, that’s very sad.

WSWS: Are there clues in Tatlin’s artistic work indicating perhaps why he did not capitulate to Stalin and the school of “socialist realism”?

DD: “Socialist realism” was a relentless, hard ideological form, intended to impact on the people via the artist, i.e., it was purely propaganda. If Tatlin had been a painter, architect or illustrator he would have had to capitulate at that time or would have ended up a martyr.

What saved him was the fact that he was a theatre artist. This meant he had the opportunity to return to the theatre as a designer after he had ended his work on the “Letatlin” [flying apparatus]. In this sphere it was the directors or scriptwriters who bore direct responsibility for the ideological orientation. He was therefore out of the firing line somewhat.

He could bring in purely artistic ideas without having to expose himself too much. That is why it was possible for Tatlin as an artist to evade “Stalinist socialism”.

Note:

[1] The 1968 exhibition at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm did not feature a single original work by Tatlin. All the objects on display were reconstructions, documents and photos. The Moscow cultural bureaucracy justified its categorical refusal to loan original works on the flimsy grounds that the latter still had to be restored and catalogued.

To be continued

Follow the WSWS