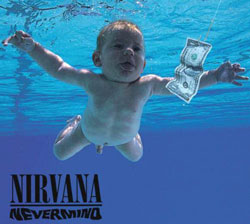

Nirvana’s Nevermind re-issued by Sony/Universal

Assessing an American pop icon

By Nick Barrickman

5 December 2012

In late 2011, a re-mastered edition of the seminal album Nevermind by pop-punk band Nirvana was released, marking the work’s 20th anniversary.

At the time of its initial release in 1991, the group’s recording label Geffen Records was forced to suspend the production of all other artists on its roster to focus on meeting the demand that the album’s release, bolstered by the hit single “Smells like Teen Spirit,” had generated. As of today, the album has gone multi-platinum in over a dozen countries, as well as being certified diamond (over 10 million copies shipped) in the United States.

At the time of its initial release in 1991, the group’s recording label Geffen Records was forced to suspend the production of all other artists on its roster to focus on meeting the demand that the album’s release, bolstered by the hit single “Smells like Teen Spirit,” had generated. As of today, the album has gone multi-platinum in over a dozen countries, as well as being certified diamond (over 10 million copies shipped) in the United States.

The re-issue of Nevermind provides the listener an opportunity to focus on some of the album’s own weaknesses and strengths, as well as the group’s enduring impact.

Nirvana—consisting of lead vocalist-guitarist Kurt Cobain (1967-1994), bass guitarist Krist (credited as Chris) Novoselic and drummer-guitarist David Grohl—emerged from the “Grunge-rock” scene, a West Coast variant of punk, which originated in Seattle, near the band’s hometown of Aberdeen, Washington, in the late 1980s. Nirvana was influenced by such groups as The Melvins and especially the American punk group, The Pixies.

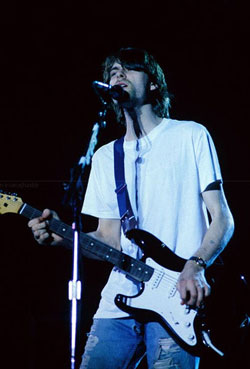

Kurt Cobain in 1993

Kurt Cobain in 1993Many of the band’s songs are unusually structured, consisting of moments of tense calm that give way to choruses characterized by abrasive, “grungy” vocals and musical accompaniment. Rather than being a superfluous element, this dynamic carried genuine aesthetic and emotional value, with many of these high-intensity switches feeling “of a piece” with the song as a whole, endowing it with an element of needed urgency.

Although this dynamic is often seen as encompassing the band’s overall sound, Cobain and the others possessed an undeniable ear for pop-sensible melodies. The underlying rhythm and bass sections work as a tandem in many instances, driving the music forward into Cobain’s more raucous crescendos.

This dynamic can be seen on songs such as the band’s break-out single “Smells like Teen Spirit”. “I find it hard/It’s hard to find/Oh well, whatever, never mind” goes the lyric of Cobain’s final verse. Feelings of disgust and angst at the existing world (“Here we are now, entertain us/I feel stupid and contagious/Here we are now, entertain us”), feelings that clearly struck a chord with a wider audience, and a willingness to buck convention prevail throughout, as each wailed chorus strongly punctuates and underscores these sentiments. From the titling of the song to its content, “Smells…” can be seen as a reference point for many of Nirvana’s strengths and weaknesses.

The title, at the time mistakenly taken from a brand of deodorant, was reportedly given to the song because Cobain thought it had a “revolutionary” sound to it. Emerging from the West Coast American punk scene of the mid-to-late 1980s, Cobain was familiar with various forms of middle class radicalism, for a time dating feminist “riot grrl” rocker Tobi Vail. For better or worse, these influences (opposition to sexism, racism and homophobia) certainly had their place in the band’s own formation.

“In Bloom” expresses the group’s desire to distance themselves from attempts to identify their music with the mostly aggressive and hedonistic imagery found in popular culture. The song criticizes individuals who “like all our pretty songs” and “like to shoot [their] gun,” but ultimately “don’t know what it means.”

“Come As You Are” contains such lyrics as: “Come, doused in mud/Soaked in bleach/As I want you to be,” with the song’s bridge possessing the provocative refrain “And I swear that I don’t have a gun.” The song’s instrumental is perhaps the catchiest on the album, with a water-like effect placed on the electric guitar that immediately draws the listener in.

Of particular note is the song “Lithium”. Intended as a depiction of religious fundamentalism and the closed-mindedness that it breeds, Cobain scathingly sings “I’m so happy/ ‘Cause today I found my friends/They’re in my head…And just maybe/ I’m to blame for all I’ve heard.” Cobain’s sarcasm is particularly biting here.

The use of sarcasm to depict the effects of religious “lithium” here also, however, points to a deeper cynicism, fueled by the artist’s own experience with “born-again” Christianity in his youth. As though simply reviling a thing were enough to get rid of it, the mocking perhaps makes up for a lack of clarity on the subject. Cobain fails to communicate how such a thing as religious obscurantism continues to have such a hold on social life, and why the artist himself may have fallen into its clutches at an earlier time. In general, processes and trends that disturb the artist are vividly identified, but not explored.

There are other weaknesses on Nevermind: the intensity of the music does tend to get tiresome, leaving the listener with very little room to reflect on what is going on. This aesthetic would come to be even more overwhelming in the band’s later efforts. With this in mind, Nirvana’s own stated opposition to anti-social and aggressive behavior seems at best to be not entirely worked through.

The album possesses more sensitive moments. “Polly” is one of the few moments on the album where Cobain appears without electric accompaniment. The song is based on the story of a local girl who had been kidnapped while at a rock concert. The singer begins cynically enough, “Polly wants a cracker/I think I should get off her first,” but one feels, in the end, his sympathies lie in the right place.

According to Cobain’s biographer Charles Cross, the name “Nirvana” was chosen for its “prettiness,” as well as suggesting to the group a connection to the ideal of “freedom from pain, suffering and the external world.” The biographer is perhaps ignoring the obvious, that “Nirvana” was the opposite of the actual conditions Cobain and his cohorts existed in.

After an ongoing and highly publicized bout with addictions, Cobain was pronounced dead in April of 1994 from a self-inflicted gunshot to the head. The singer-songwriter was 27 years old.

Philistine commentators will always attribute the suicide of such a personality to purely private, individual difficulties. Those, of course, play a significant role. Except in the most extreme cases, social life does not directly lead to someone laying hands on himself. However, in the case of a public figure as sensitive and alive to external stimuli as Cobain, one can’t help but consider the social period in which his and the band’s rise to prominence occurred, as well as the various social processes that molded their outlook.

Whatever longing the band’s name suggests, it must also have referred, ironically, to the atmosphere of the time, with its worship of money, greed and militarism. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the “end of socialism,” if not the “end of history,” meant, according to the official doctrine, that the present state of things was the best of all possible worlds. What a bleak and debilitating prospect!

These socio-psychic conditions, in our view, had a great deal to do with the tragic path that Cobain’s own life would take.

For someone alive to the filthiness of this spectacle, without a clear conception of what was occurring or any hope that it might change, the urge to run and “escape” must have been overwhelming.

Cobain, Grohl and Novoselic undoubtedly possessed immense talents and a natural chemistry together. One can only speculate about what Cobain would have been capable of creating had his own life and condition generated better prospects.

Follow the WSWS