Jazz musician Dave Brubeck dies at 91

By Hiram Lee

10 December 2012

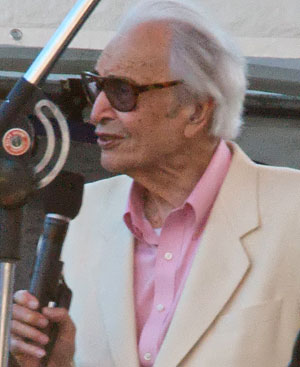

Brubeck at the 2009 Detroit Jazz Festival

Brubeck at the 2009 Detroit Jazz FestivalJazz legend Dave Brubeck died December 5 in Norwalk, Connecticut, just one day before his 92nd birthday. The renowned pianist and composer had been traveling to a regular appointment with his cardiologist when he suffered a heart attack.

Brubeck was a significant figure in postwar jazz and American culture. A popular figure in the 1950s and 60s, his classic 1959 album Time Out sold a million copies, the first jazz album to hold that distinction. Always a serious and intelligent musician, many of Brubeck’s best compositions, including “The Duke,” “In Your Own Sweet Way,” and “Blue Rondo à la Turk,” merit repeated listening.

Dave Brubeck was born December 6, 1920, in Concord, California—some 30 miles east of San Francisco—and grew up in a musical family. His mother, a classically trained pianist, began teaching her son the instrument at the age of four. He developed a love for jazz music early on and was performing by the time he was a teenager.

While Brubeck certainly performed in dance bands and in nightclubs, he developed in a mostly academic environment. Attending the College of the Pacific in Stockton, California, with the intention of becoming a veterinarian, he instead became a music major. After graduation and a stint in the army beginning in 1942, Brubeck would go on to study with French-Jewish modernist composer Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) at Mills College in Oakland, California. (Milhaud had fled to the US to escape Nazism.) The experience had a profound and lasting impact on the young musician, so much so that Brubeck would name his first son Darius in the composer’s honor.

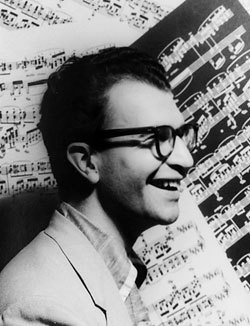

Brubeck in 1954

Brubeck in 1954Brubeck would make his first recordings as a bandleader by the end of the decade. Stylistically, his music shared many of the traits of the then-emerging West Coast or “Cool” jazz style, although he was not a central figure in that movement as he is sometimes made out to be. His interesting octet recordings of the late 1940s do, however, bear some similarities to the music being made at the same time by Miles Davis and cool jazz pioneer Gerry Mulligan on the East Coast.

The work for which Brubeck remains best known is that performed with his classic quartet featuring Paul Desmond on alto saxophone, the remarkable drummer Joe Morello and bassist Eugene Wright. Formed in 1958, the group worked together until 1967.

The Dave Brubeck Quartet were well known for their “Time” albums—Time Out, Time Further Out, Time Changes, etc.—on which they experimented with complex time signatures beyond the standard 4/4 or 3/4 most common in jazz. “Blue Rondo à la Turk,” one of the group’s best, was in 9/8 time. The catchy “Unsquare Dance” was in 7/4. “Eleven Four” was, of course, in 11/4.

Dave Brubeck Quartet at Congress Hall Frankfurt/Main (1967). From left to right: Joe Morello, Eugene Wright, Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond.

Dave Brubeck Quartet at Congress Hall Frankfurt/Main (1967). From left to right: Joe Morello, Eugene Wright, Dave Brubeck and Paul Desmond.The group’s most famous song, “Take Five,” written by Desmond, is in 5/4 time, feeling slightly like a waltz. The “cool” melody played by Desmond’s light and airy alto saxophone is unforgettable. A wonderful solo from Morello, in which he makes great use of space and repetition, is perhaps the song’s greatest asset. Listen on YouTube.

While the Quartet contained two extraordinary soloists in Desmond and Morello, Brubeck’s own playing could be somewhat stiff and academic. His famous densely chorded solos could on occasions overwhelm the natural flow of the music. But at his best he could deliver genuinely inspired moments. The lengthy solo piano introduction to “Strange Meadow Lark” from Time Out is beautiful, as are the many simple but elegantly phrased solos found throughout that album. While Brubeck was not the greatest jazz pianist of his generation, there is something that draws one’s ear and brain back to him again and again.

More than anything, it was the way the group performed together rather than the work of this or that member that one admires about the famous quartet. An excellent example of the group as a dynamic and exciting ensemble in live performance can be found on the very good At Carnegie Hall album of 1963. Listen on YouTube.

Along with his musical talents, Brubeck was also a man of considerable personal integrity and honesty. A staunch opponent of racism, Brubeck again and again came up in opposition to the segregationist policies of music venues throughout the country. He refused to play in those venues that attempted to book him on the condition that he not perform with the group’s African-American bassist Eugene Wright. In 1958, Brubeck refused to tour South Africa, and turned down a nearly $20,000 fee ($160,000 in 2012 dollars), a large sum for a musician, when authorities insisted that his band contain only white musicians.

In 1967, the Dave Brubeck Quartet disbanded and Brubeck devoted himself to composing more-ambitious works for larger ensembles. He composed ballets, musicals, cantatas, oratorios and much more. In 1972, he composed “The Truth Has Fallen,” as a tribute to the students killed by National Guard troops at Kent State University in 1970.

Brubeck would form other small combos throughout his later career, including groups featuring his sons, now successful musicians like their father, but none would capture the special qualities of the classic quartet.

He would remain active in music for the remainder of his life. Brubeck’s name was among this year’s Grammy nominees in the category of Best Instrumental Composition. He was nominated for a symphonic work composed with his son Chris entitled “Music of Ansel Adams: America” and performed by the Temple University Symphony Orchestra. Dave Brubeck: In His Own Sweet Way, a 2010 documentary, is a useful introduction to his life and work.

Follow the WSWS