The Central Park Five: A story of injustice

By Joanne Laurier

12 December 2012

The Central Park Five has opened in theaters in the US and will be released more widely over the next two weeks. Joanne Laurier discussed the film as part of the WSWS coverage of the 2012 Toronto International Film Festival: “Filmmakers respond to important events—but how they respond is also important…” . We repost a slightly edited version of that comment today.

The Central Park Five

The Central Park FiveIn New York City in 1989, five minority youth aged 13 to 16 were arrested and convicted in the rape and near-murder of a 28-year-old white female investment banker, Trisha Meili, who was jogging in Central Park. The incident dominated the headlines of the tabloids for weeks, as the gutter press took the seemingly golden opportunity to whip up hysteria against black working class youth.

The victim in the assault suffered from memory loss as a result of her injuries and was unable to identify her attackers.

The innocent black and Latino teenagers from Harlem spent between 6 and 13 years in prison before a serial rapist confessed to the crime. Directed and produced by renowned documentarian Ken Burns, daughter Sarah Burns, who has written a book about the case, and her husband David McMahon, The Central Park Five chronicles the case, focusing on interviews with the now-adult men who suffered appallingly at the hands of a vindictive and unjust legal structure and media.

At the time of the tragic incident in Central Park, social tensions were high, as deteriorating economic conditions and budget cuts helped generate record levels of violent crime, and the city’s elite was demanding a crackdown.

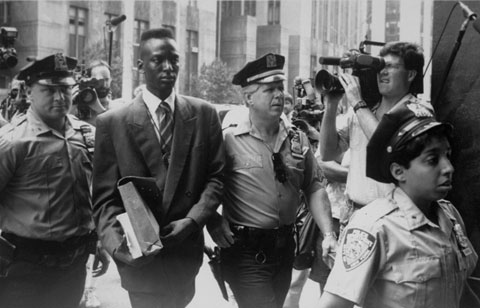

Following the brutal attack on Meili, a police dragnet against minority youth led to the rounding up of Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise and Yusef Salaam, who “confessed” to the Central Park attack after 14 to 30 hours of aggressive interrogation by police.

The Central Park Five

The Central Park FiveThe New York media went into a frenzy against the teens, who it claimed were out “wilding,” running in a “wolf pack” after their “prey.” Mayor Ed Koch called the boys “monsters,” claiming that this would be a test case for the death penalty. Real estate billionaire Donald Trump took out full-page ads in all four of the city’s dailies, headlined “Bring Back the Death Penalty, Bring Back Our Police.” New York Times liberal black columnist Bob Herbert coined the expression “teenage mutants.”

Careers in the police department and the prosecutors’ office were made at the expense of the persecuted teenagers. The young men were tried and convicted despite a lack of evidence, including any DNA proof. Burns’s movie offers a sympathetic platform to the victims and their families, whose determined quest for justice contrasted starkly with the callous indifference and criminality of the police, the judicial system, Democratic Party politicians and their media accomplices.

In 2002, based on the confession of Matias Reyes, a judge vacated the original conviction of the Central Park Five. Civil lawsuits filed by the men against the City of New York and the police officers and prosecutors who worked for their convictions remain unresolved.

This is a case absolutely worth revisiting, but the filmmakers’ decision to present it almost entirely in racial terms is an error. The vast prison population in the US, which includes both those who are innocent of the crimes for which they are charged and those whose primary crime is being poor, are victims of the present social inequality and blighted character of American capitalism.

The filmmakers downplay this dominant reality. Says Ken Burns in the movie’s press notes: “This tragedy reminds us how much we struggle to come to terms with America’s original sin, which is race.” The profit system is the original sin, and race is used as one of its preferred means of dividing and conquering. The film itself shows that the political and media offenders are both black and white.

Moreover, the Toronto film festival this year also screened the latest installment in the saga of three white Arkansas men, known as the West Memphis Three (West of Memphis, directed by Amy Berg), who as teenagers shared a similar fate to that of the Harlem teenagers. In deliberately narrowing the scope of The Central Park Five, the Burns team implies, by what it leaves out, that the case is an unhappy exception rather than one episode in an ongoing social disaster. The best intentions cannot make up for this sort of social semi-blindness.

Follow the WSWS