Howl: Allen Ginsberg and American culture in the 1950s

By Kevin Martinez

10 December 2010

Howl

HowlDirected by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman

“All these books are published in Heaven.”

In 1955 Allen Ginsberg composed an innovative poem in Berkeley, California entitled “Howl”. Its opening lines, “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by/ madness, starving hysterical naked,/ dragging themselves through the negro streets at dawn/ looking for an angry fix,” are well-known and oft-quoted. The words speak evocatively and powerfully to the terrible political and social dilemmas of postwar America, those facing the younger generation in particular.

Ginsberg and his contemporaries Jack Kerouac (On the Road) and William S. Burroughs (Junkie) became icons of the Beat generation, and later, venerated figures in the burgeoning “counter-culture” of the late 1960s and early 1970s. They were painted as rebels who had done what they pleased in the repressed, monolithically conservative era known as the Eisenhower years.

Howl, the recent film adaptation by Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, is a non-linear work composed of three central elements: a black-and-white recreation of the poem’s debut at the Six Gallery in San Francisco on October 7, 1955; a reenactment of the subsequent obscenity trial involving poet and editor Lawrence Ferlinghetti who published the poem; and flashbacks to the writing process that produced the poem, with Ginsberg speaking to an unseen interviewer.

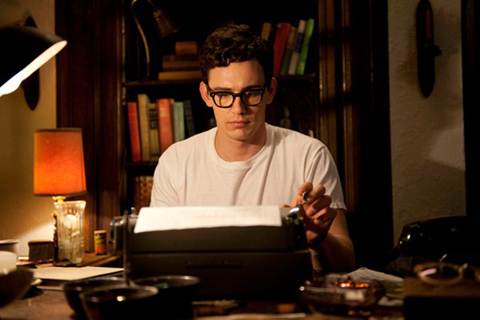

In addition to the poem, which is read in its entirety, the filmmakers have included well-done animation and visceral computer-generated sequences. Actor James Franco, a talented performer, portrays Ginsberg with appropriate vulnerability and sensitivity.

If the creators of Howl merely aspired to make an intelligent and entertaining companion piece to the poem itself, they have succeeded. If, however, their intention was to make a work that served as wider commentary on the life and times of Ginsberg and his colleagues, then Howl falls short. What is lacking, in this reviewer’s opinion, is more of the historic and social context.

Various names are dropped in the film, faces come and go, but the spectator is expected to know everyone. We are introduced to Neal Cassady, Kerouac, and Ferlinghetti, but they are not given any substantive lines, despite the fact that these were important Beat writers and personalities. Only Ginsberg’s character is fleshed out. Although the filmmakers have made a conscious effort to play with different strands of the story--e.g., courtroom scenes are juxtaposed with images of Ginsberg’s earlier life, followed by animated sequences that accompany the poem itself being read for the first time--more thought and depth could have being given to the history of 1950s America.

When Ginsberg was typing away on “Howl,” many things, aside from the purely personal, must have swirling around in his head: the painful results of the anti-communist witchhunts and the tragic fate of a generation or more of American leftists (including members of his family); the celebration of conformism and consumerism associated with the mid-1950s’ economic boom; the birth of the civil rights movement, and more. These developments find only a fleeting expression in Howl, the film.

The filmmakers choose to focus on the poet’s homosexuality. Franco’s Ginsberg explains how “Howl” came about in reaction to the dominant sexual mores, “If you can write about homosexuality, you can write about anything.” However, sex is only one aspect of a very complicated process, namely the struggle to be inspired enough to create lasting art.

One of the more memorable moments in the film occurs when Ginsberg is staring at what appears to be a painting by Cézanne and says, “What prophecy actually is, is not knowing whether the bomb will fall in 1942, it’s knowing and feeling something which someone knows and feels in a hundred years, and maybe articulating it in a hint that they will pick up on in a hundred years.”

A significant part of the film details how Ginsberg wound up in a mental hospital, his only escape then being to tell the doctors, lyingly, that he would pursue nothing but heterosexual relationships from then on. His companion in the institute, Carl Solomon, to whom the poem is dedicated, was not so lucky. He received electro-shock therapy and put in a strait-jacket. Ginsberg’s mother, Naomi, was in a mental institution before she died an early death. This difficult personal history is integrated into the film movingly and sincerely.

Perhaps Howl’s greatest strength, and where most of its real drama emerges, is its recreation of the famous 1957 obscenity trial. US customs officials seized 520 copies of the poem on March 27, 1957. In court attorney Jake Ehrlich (Jon Hamm) defends City Lights publisher Ferlinghetti (Andrew Rogers) against charges that Ginsberg’s “Howl” is “obscene material” and therefore harmful to the general public.

Ehrlich strongly argues not only for the language, but the spirit of “Howl,” in front of a host of philistine academics and conservative prosecutors. Not only are the critics taken aback by the highly sexual imagery and frank discourse of the poem, but its radical politics as well. The judge in the case eventually determined that the poem had “redeeming social importance.”

Much has been written about the various drug escapades and mysticism indulged in by Ginsberg and his Beat friends, but however individually foolish they may have been in this regard, their carryings-on need to be seen as a response as well to the world in which they found themselves after World War II.

Some of the self-destructive and despairing sentiments of the time are evident in Ginsberg’s poem, when he writes of those “who burned cigarette holes in their arms protesting/ the narcotic tobacco haze of Capitalism,/ who distributed Supercommunist pamphlets in Union/ Square weeping and undressing while the sirens/ of Los Alamos wailed them down, and wailed/ down Wall, and the Staten Island ferry also/ wailed/ who broke down crying in white gymnasiums naked/ and trembling before the machinery of other/ skeletons.”

Many of Ginsberg’s generation had gone to war, returned home and even went to college, but could not fit in because they were still traumatized by their experiences or were appalled by the reality of Cold War America. Kerouac, for example, had been a merchant seaman during the war. Intellectual life was seriously damaged by the McCarthyite witchhunts and liberalism’s embrace of anti-communism. Small wonder then that some young people turned Buddhist in a reaction to Christianity or roamed the country like nomads with no permanent homes.

Ginsberg identified the source of the evils in his poem as “Moloch,” the ancient Semitic god to whom children were sacrificed. He meant the horror of capitalism, “whose soul is electricity and banks!,” The would-be censors in 1957 were deeply disturbed. This portion of “Howl” is constructed through images of boys marching off to war, filling rows and rows of coffins, and mountains of skulls inside a demonic treasury. It is difficult not to the think of the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan when reading this sequence.

Toward the end of the Epstein-Friedman film, the attorney, Ehrlich, defends Ferlinghetti’s decision to publish “Howl” by asking, “What is prurient? And to whom? The material so described is dangerous to some unspecified, susceptible reader. It is interesting that the person applying such standards of censorship rarely feels as if their own physical or moral health is in jeopardy.” It is an interesting and courageous moment that certainly resonates in our self-censoring, government-policed culture of today.

Finally, Ginsberg finishes his ode to Solomon with the words, “I’m with you in Rockland [the mental hospital]/ where there are twenty five thousand mad com-/ rades all together singing the final stanzas of the Internationale,” and adds in a footnote, “Holy the Fourth Dimension, Holy the Fifth International,” which he prophesized was yet to come. A frenzied but generally optimistic ending to the suffering and pain he describes.

The film’s coda explains that Kerouac died in 1969 at age 47, while legendary Beat hero Cassady died in 1968 at age 41. Why so young? The film leaves the question unanswered, although something of the tragedy--and dead end--of their bohemianism emerges. The essential subject matter of Howl, American politics and culture in the postwar period, is an extremely complex phenomenon, to which we return time and time again.

Follow the WSWS