The “Hegel renaissance” and other questions

A comment on The Cambridge Companion to Hegel and Nineteenth-Century Philosophy

By Alexander Fangmann

5 November 2009

The Cambridge Companion to Hegel and Nineteenth-Century Philosophy, edited by Frederick C. Beiser. Cambridge University Press, 2008 New York and Cambridge (UK). Paperback (ISBN-13: 9780521539388), $32.99.

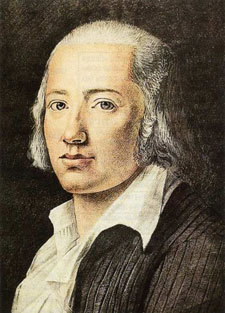

Hegel

HegelLast year saw the publication of The Cambridge Companion to Hegel and Nineteenth-Century Philosophy, edited by Frederick C. Beiser. The volumes of the Cambridge Companion series contain collections of essays by scholars working on a particular philosopher or subject area. They are intended to be introductory reference works to their subject matter and frequently serve as college textbooks at both the undergraduate and graduate level. Their editors and contributors are generally well-respected by other professional philosophers, and the series tends toward the inclusion of newer research. For that reason, the essays they contain may be indicative of the current state of scholarship among a wide layer of people in and around academic philosophy. The intention of the present article is to survey some of the more interesting findings of this research and comment on some of its limitations.

As Beiser indicates in his editorial introduction, “The Puzzling Hegel Renaissance,” since the publication of The Cambridge Companion to Hegel in 1993, there has been a notable growth of interest in Hegel and a vast increase in the quantity of scholarly work on his philosophy. According to Beiser, this—along with the absence of essays on certain topics in the first Hegel-themed Cambridge Companion, such as Hegel’s philosophy of nature and philosophy of religion, and a desire to include the work of younger scholars, as well as newer essays by more established ones—justified the production of this new collection of essays.

Although its title would suggest an emphasis on the relationship between Hegel’s work and that of other nineteenth-century figures, such as Marx, for example, it is conceived, as indicated in Beiser’s preface, more as a second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Hegel, albeit with a new set of essays. References to other philosophers and thinkers are mostly limited to Hegel’s contemporaries, predecessors, and even more remote historical thinkers. In fact, while the original Cambridge Companion included the essays “Hegel and Marxism,” by Allen Wood, as well as “Hegel and Analytic Philosophy,” by Peter Hylton, this new volume contains no essays, outside of Beiser’s introduction, which deal directly with the reception of Hegel’s thought after his death in 1831.

This is a very serious limitation, and represents a step backward from earlier periods in Hegel studies. The very idea that one can understand Hegel without examining the reception of Hegelian ideas by other thinkers, particularly Marx, is absurd and retrogressive. Hegel’s ideas are not merely the artifacts of an isolated genius; their true significance and meaning can only be gauged by their reception and development. Marx and Engels delivered not only the most devastating criticisms of the Hegelian system, they were also the first thinkers to appreciate the theoretical advances made by Hegel and place them on a scientific and materialist basis. Without them, it is quite possible that this volume would not exist, given the continuous effort by philosophers of various persuasions to bury Hegel and turn towards the manifold forms of subjectivism (Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, the Neo-Kantians, the positivists, etc.).

Beiser attempts to provide an explanation for this apparently strange phenomenon: the relatively recent growth of intense interest in Hegel on the part of professors of philosophy. As he says, “Such a surge in interest is remarkable for any philosopher, but especially for one who, some fifty years earlier, would have been treated as a pariah.” (1) It is no great secret that academic philosophy in the English-speaking countries has largely ignored Hegel, considering him to be at best hopelessly obscure, and at worst a dangerous charlatan responsible for providing an intellectual basis for fascism and Stalinism. James Burnham’s characterization of Hegel in “Science and Style” as “the century-dead arch-muddler of human thought” still represents the opinion of a considerable faction of philosophers.

Much of the antipathy towards Hegel finds its source in the fact that his thought was seen to lead to Marx and Marxism. But, as Beiser acknowledges, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the eastern European Stalinist states, “Marxism suffered—for better or worse—a steep decline in prestige. But as Marx’s star fell, Hegel’s only rose.” The clear implication is that with Marxism out of the way Hegel could again be seen as politically non-threatening, and he “was restored to the pantheon of great philosophers, taking his place alongside Leibniz and Kant.” (2) So much for judging philosophical works based on the soundness and validity of the arguments! This statement is a rare admission that political considerations are a substantial factor in their acceptance or rejection by the academy.

In the rest of his essay, Beiser explains that much of the credit for the revival of interest in Hegel can be credited to scholarly interpretations which have “anachronistically” interpreted Hegel in order to further contemporary philosophical concerns. Representative of this “anachronistic” approach, in Beiser’s estimation, are Robert Pippin and Robert Brandom who, while differing in many respects, have greatly downplayed the metaphysical and religious dimensions of Hegel’s thought in order to make it more palatable to contemporary philosophical tastes, while presenting their interpretations as Hegel’s own position. While he admits that such work has been interesting, Beiser advocates that future work take a more “antiquarian” interest in Hegel, finding out what his actual positions were and why he held them, and only later worrying about their applicability to contemporary philosophical concerns.

While it is true that Pippin’s interpretation of Hegel has been highly influential, at least among the professoriat, it must be said that his approach is not merely “anachronistic”—it is highly revisionist. Pippin’s Hegel is a Kantian, committed to Kant’s basic framework and to carrying out his project in regard to providing a subjective foundation for the external world. This line of interpretation ignores Hegel’s ruthless criticisms of Kantianism, and especially of Kant’s restrictions on human reason and knowledge, and this ultimately results in a subjectivist version of Hegel. Given the widespread acceptance of such notions in the academy, it is perhaps no surprise that Pippin’s work has found a substantial audience. Beiser’s collegial and muted criticisms of Pippin and others putting forward similar arguments, are unfortunate. Their work requires a more thorough and systematic debunking if any substantial progress in Hegel scholarship is to be attained.

Hegel’s biography

Terry Pinkard’s contribution, “Hegel: A Life”, a shortened version of his book, Hegel: A Biography, places Hegel’s intellectual labors within their proper personal and historical context. Despite the limitations of Pinkard’s philosophical orientation, his historical work is nonetheless quite interesting and useful. Among the more interesting things we find out about Hegel is his background in the Württemberg petty-bourgeoisie. His father was a minor official at the Royal Treasury, and his mother came from a family of Swabian Protestant reformers. Although possessed of a somewhat provincial pride in their particular Protestant and local traditions, they were receptive to the new ideas circulating at the time, and subscribed to the “Enlightenment-oriented journals of their day.” According to Pinkard, “they based their claims to rank and promotion on learning and ability, not on family connections.” (17)

This attitude towards social position would stay with Hegel his whole life, with the consequence that he maintained all sorts of acquaintances, and would play cards with “nonacademic types” and maintain friendships “with both the artistic and the more bohemian elements in Berlin society.” (41) His belief that talent, and not wealth or connections, should be decisive for career and advancement expressed itself in his waiving of student lecture and examination fees for poorer students, at a time when such fees constituted part of the regular pay of university instructors. A criticism he leveled at the English in his writing on the English Reform Bill was that instead of “university education and science, they value the ‘crass ignorance of fox-hunters.’” (49)

Friedrich Hölderlin

Friedrich HölderlinThe impact of the French Revolution on Hegel and his thought is a common theme. In 1789, Hegel was a student at the Protestant Seminary in Tübingen who had recently decided that he did not want to be a clergyman, a sentiment shared by his fellow students and roommates, Friedrich Hölderlin and Friedrich Schelling (the former a highly influential and original poet, while the latter might have been the most influential German idealist philosopher had Hegel not eclipsed him in importance). Because the duke of Württemberg held some lands in Alsace, news of the revolution made its way to the seminary “with even more speed and regularity than it did elsewhere.” (19)

Friedrich Schelling

Friedrich SchellingThe trio were greatly enthusiastic about the events in France, and their views were reinforced by one of the more senior students at the seminary, Carl Immanuel Diez, a radical Kantian and Jacobin sympathizer who saw an essential unity between Kant’s philosophy and the revolutionary calls for liberty, fraternity, and equality. Every July 14 from then on, Hegel would toast the storming of the Bastille, and near the end of his life, in his lectures on the philosophy of history at the University of Berlin, he would refer to the revolution as a “glorious dawn.”

In the wake of the revolution, governments throughout Germany embarked on reform projects, some by way of Napoleonic invasion, such as Bavaria, and some out of fear of revolution. From 1807 to 1808, Hegel edited a pro-Napoleonic newspaper, the Bamberger Zeitung, until he got into trouble with authorities for “publishing information about French troop movements that had already been published in other newspapers.” (31) This episode apparently induced him to leave journalism, and he would appeal to his friend, Immanuel Niethammer, to get him a teaching job at a university. Niethammer was an old friend from his seminary days who had become commissioner for educational reform in Bavaria. Wanting an ally, he appointed Hegel rector of a Gymnasium in Nuremberg, a position in which the latter flourished, later with the added responsibility of being the inspector of schools for Bavaria. Hegel’s fortunes would often depend on the influence of reformers in government, and he in turn would often intervene in the intellectual debates surrounding political issues, and later into such issues more directly.

One of the first things many people learn about Hegel is that he was an apologist for the Prussian state, with his proposition that “what is rational is actual, and what is actual is rational.” This is the phrase with which he ended the preface to the Philosophy of Right, which was published in 1820. Based on the surrounding events that Pinkard describes, it is no surprise that nearly everyone interpreted the statement to be a defense of repressive government. In that same preface Hegel had included attacks on the philosopher J.F. Fries and the theologian Wilhelm de Wette. Both had lost their teaching jobs due to being characterized or charged as “demagogues” in the wake of the reactionary Carlsbad Decrees, enacted by Metternich throughout the German Confederation in the wake of the assassination of the conservative writer August von Kotzebue. Hegel’s attack on the two thinkers was seen as support for the charges against them. But, according to Pinkard, “Hegel was taken aback at this interpretation” of his proposition and went so far as to influence the creation of an encyclopedia entry to deny that it was intended “for the benefit of the ruling classes.” (41)

Hegelian dialectics and the Science of Logic

Hegel’s Logic has been mostly ignored as a subject of serious scholarship, and the dialectical method that Hegel employs has been the object of much derision, misunderstanding, and outright falsification. Both the Science of Logic and the shorter Encyclopedia Logic (intended as a lecture outline for his students) are difficult works, and are not widely taught in philosophy courses, even by Hegel specialists. For that reason, “Hegel’s Logic,” by Stephen Houlgate, which attempts to “shed light on the distinctive purpose and method of Hegelian logic,” is to be commended. Houlgate’s contention is that Hegel in these works attempted no less than to “derive and clarify the basic categories of thought.” (112)

It is impossible to do justice to Houlgate’s lengthy contribution within the limits of this review. Let suffice a gloss on some of the more interesting themes he touches upon. The first of these concerns the starting point of the Logic, which is the category of “being.” Rather than a purely arbitrary or mystical beginning, or one that conceals underlying assumptions and presuppositions in order to move the argument, Houlgate argues that Hegel is in fact trying to start from the most critical position possible.

In the spirit of Descartes’ universal doubt, Hegel starts with thought “at its simplest and most minimal.” Thought at its simplest and most minimal, however, does not entail such extravagant implications as Descartes supposed, namely the existence of the thinker, at least at the outset of the investigation. Thought, stripped of all particularity, that takes “as little as possible for granted,” must understand that “what is thought, is.” In other words, the fact that there is thought implies that there is something to think about. But this something must not be assumed to have any characteristics whatsoever, in order for the investigation in the Logic to remain fully critical. It can only be considered insofar as it is, insofar as it is being at its most abstract. (120)

In the course of investigating this initial category of being, at its most abstract and indeterminate, “it vanishes before our eyes into nothing.” (128) Without any distinguishing characteristics, the thought of pure being is completely empty, and is practically equivalent to the thought of nothing. But this nothing can only be thought insofar as it is something, and so nothing falls back into being. A nothing that can be thought is, and so it is no longer nothing, but is a type of being. Each of these pure categories “turn out to be logically unstable and to disappear into the opposite of itself... each proves to be nothing but the process of its own disappearance.” What they are is, in fact, a “becoming.” (129)

The rest of the Logic proceeds along lines similar to those shown above in regard to being, nothing, and becoming, insofar as every successive concept gives way to another while remaining intimately related to all the concepts preceding it—although there are of course several variations in the movement from one category to another. By the time he has finished, Hegel has attempted to address every general concept and category of thought and has shown their proper relation to each other. While previous thinkers were more or less content to accept basic logical and conceptual categories as axiomatic—given and indubitable—or as plain common-sense, Hegel believed that science needed a rigorous exposition and investigation of its most fundamental concepts.

Although these categories do turn out to be essentially related to each other, this relatedness is something that Hegel claims not to presuppose, at least for his arguments. The dialectical character of these conceptual relationships is therefore not something that he is imposing on the subject matter. As Houlgate puts it, “although Hegel does not presuppose that speculative thought should be dialectical, such thought does in fact prove to be dialectical of its own accord. Dialectic, for Hegel, is not a relation between different things (for example, between an individual and society), but is the process whereby one category or phenomenon turns into its own opposite.” Further, “Dialectic is thus not a method devised by Hegel and brought to bear on categories from the outside, but belongs to those categories (and corresponding aspects of being) themselves. It is the ‘inwardness of the content, the dialectic which it possesses within itself.’” (129-130)

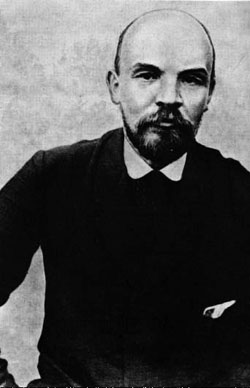

V.I.Lenin

V.I.LeninHowever, as good as Houlgate’s essay is, it shares with other scholarship on this topic a noticeable and unfortunate tentativeness—a lack of conviction and confidence—which arises from the fundamental confusion and wrangling over basic philosophical categories which pervades contemporary philosophy. This is quite different from what one encounters in Lenin’s Philosophical Notebooks in his notes and comments on Hegel’s Logic. Fragmentary as they are, these writings gain much in value from Lenin’s correct appreciation of the fundamental questions of philosophy at issue, especially on the question of the relation between materialism and idealism. Although Lenin gave the most detailed and important materialist critique of Hegel’s Logic, this advance has been totally ignored by the philosophical establishment.

Hegel’s idealism

Robert Stern’s contribution to The Cambridge Companion to Hegel and Nineteenth-Century Philosophy on the broad subject of Hegel’s idealism is an effort to sort out precisely what the great German philosopher’s idealism amounted to. While it is certainly clear from a materialist perspective that Hegel was an idealist, it is by no means a simple matter exactly what this means.

According to Stern, Hegel is an idealist thinker in two slightly different, but closely related senses. His claim is that Hegel “is an idealist in his special sense, of holding that ‘the finite is ideal,’ and (therefore) an idealist in the more classical (antinominalist) sense of holding that taken as mere finite individuals, things in the world cannot provide a satisfactory terminus for explanation, but only when they are seen to exemplify ‘universals, ideal entities’ … which are not given in immediate experience, but only in ‘[reflective] thinking about phenomena.’” (172)

In order to understand these two senses of idealism at work in Hegel, it is helpful to refer to a passage from the Science of Logic which Stern quotes more fully in his essay: “The proposition that the finite is ideal [idell] constitutes idealism. The idealism of philosophy consists in nothing else than recognizing that the finite has no veritable being [wahrhaft Seiendes]. Every philosophy is an idealism, or at least has idealism for its principle and the question then is how far this principle is actually carried out. This is as true of philosophy as of religion, for religion equally does not recognize finitude as a veritable being [ein wahrhaftes Sein], as something ultimate and absolute or as something underived, uncreated, eternal …

“A philosophy which ascribed veritable, ultimate being to finite existences as such, would not deserve the name of philosophy; the principles of ancient or modern philosophies, water, or matter, or atoms are thoughts, universals, ideal entities, not things as they immediately present themselves to us, that is, in their sensuous individuality—not even the water of Thales. For although this is also empirical water, it is at the same time also the in-itself or essence of all other things, too, and these other things are not self-subsistent or grounded in themselves, but are posited by, are derived from, an other, from water, that is they are ideal entities.” (SL 154-155)

When he says that the “finite is ideal,” Hegel means that objects, the ordinary, everyday things one encounters are not purely material, but are, in some sense, actually constituted by ideas. Of course, for Hegel these are not just any ideas, but the conceptual categories worked out in the Science of Logic. These concepts are not concepts that operate only in human reason, but the concepts to which reason is led necessarily by reflecting on the mere idea of being. These concepts are objective, and all objects are constituted by some combination of them, depending on what sort of things they are, that is, by their concrete character. Furthermore, since all these concepts are moments of the Absolute Idea, or the Hegelian infinite, these objects are related to and owe their reality to the Absolute.

Nominalism is the philosophical position that universals—abstract concepts like red, sweet, or good that are applied to many things—do not actually exist in themselves, but that there are only individual objects and properties. According to nominalists, these “universals” are only words we use to group similar characteristics as a convenience. Historically, idealism has been connected with a position of anti-nominalism (a position also somewhat perversely known as realism) by holding that these universals are just as real, if not more so, than material objects.

Hegel is opposed to nominalism, in its modern forms often associated with empiricism, because it supposedly follows that there is no essential unity to the world and no fundamental relationships between objects. Rather, there are only individual things which are associated, at best, only contingently. A philosophy built on such a premise (which ascribed veritable being to finite things) would be, for Hegel, a non-philosophy.

This is because any investigation which considered only these things would be incomplete, it would not have the conceptual resources to fully explain the way the world works. For all previous philosophy, what explains why things are what they are, and how they are able to relate to each other, is some principle or other, such as atoms, matter, or (for Thales) water. What these things all have in common is that they are conceptual abstractions—atoms and matter as such have not been perceived, nor has water in the way it is conceived of by Thales to be the essence of all things. But as opposed to finite material things, which in their course come to be and pass away, this infinite matter, or atoms, or water, does not, and is thus what is truly real.

Although he treats some intriguing questions, it must be frankly noted that Stern’s essay is not very helpful for someone interested in the nature of Hegel’s idealism. He is writing in a philosophical milieu itself steeped in idealism, and which denies this more or less consciously. This makes it impossible for him to formulate an objective initial characterization of idealism.

Stern rejects early on a somewhat promising line of investigation, in which Hegel is an idealist due to his view of “the absolute mind as the transcendent cause or ground of the world,” because it would amount to a rejection of Kant’s separation of appearances and things-in-themselves, and a return to a “pre-critical” metaphysics. Not only is this a fundamental error regarding Hegel’s relationship to Kant, which passes over his devastating criticisms of the Kantian system, it also leads Stern to embark on an essay in which a concept of idealism is sought in Hegel’s own work, a strategy that is problematic, to say the least.

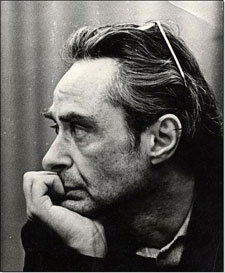

Evald Ilyenkov

Evald IlyenkovFar more valuable is the characterization of Hegelian idealism made by the Soviet philosopher Evald Ilyenkov, in his book Dialectical Logic (1974). In that remarkable work Ilyenkov explains how human thought could be transformed by Hegel into the impersonal and God-like Absolute, imposing itself on all human actions and history:

“Hegel actually counterposed man and his real thought to impersonal, featureless—‘absolute’—thought as some force existing for ages, in accordance with which the act of ‘divine creation of the world and man’ had occurred. He also understood logic as ‘absolute form,’ in relation to which the real world and real human thought proved to be something essentially derivative, secondary and created.

Ilyenkov argues that Hegel’s specific form of objective idealism converted thinking into a new deity, into a force existing outside humanity and dominating it. However, Hegel’s illusion in this regard did not constitute simply a borrowing from religion, or a mere unfortunate recurrence of religious consciousness, as Feuerbach suggested, but came from a more profound source.

The Soviet philosopher continues: “Under the spontaneously developing division of social labour there arose of necessity a peculiar inversion of the real relations between human individuals and their collective forces and collectively developed faculties, i.e. the universal (social) means of the activity, an inversion known in philosophy as estrangement or alienation.”

Certain universal modes of action were organized as special social institutions, established as trades and professions—as a type of caste with its own specific language, traditions and so on—and other structures of an impersonal, featureless character.

Ilyenkov goes on: “As a result, the separate human individual did not prove to be the bearer, i.e. to be the subject, of this or that universal faculty (active power), but, on the contrary, this active power, which was becoming more and more estranged from him, appeared as the subject, dictating the means and forms of his occupation to each individual from outside. …

“The same fate also befell thought. It, too, became a special occupation, the lot for life of professional scholars, of professionals in mental, theoretical work. Science is thought transformed in certain conditions into a special profession. … The scientist, the professional theoretician, lays down the law to them [ordinary humanity] not in his own name, personally, but in the name of Science, in the name of the Concept, in the name of an absolutely universal, collective, impersonal power, appearing before other people as its trusted representative and plenipotentiary.

“On that soil, too, there arose all the specific illusions of the professionals of mental, theoretical work, illusions that acquired their most conscious expression precisely in the philosophy of objective idealism, i.e. of the self-consciousness of alienated thought.” (Dialectical Logic, Chapter 7)

Ilyenkov here is operating with a much more precise and profound conception of idealism, in which, first of all, the fundamental criterion separating idealism and materialism is the question of whether thought (spirit) or nature is considered primary and which is secondary. On this basis is it easy for him to establish that Hegel is an idealist, and through a materialist understanding of history, he is able to explain the specific nature of Hegel’s idealism which separates it from all others.

Yet, Ilyenkov’s work is almost entirely ignored amongst professional philosophers, as is the work of a number of other Soviet philosophers who made important contributions to philosophy, even while working under the restrictions imposed by the Stalinist regime. This continued blockade on these Soviet thinkers can only be regarded as intellectual bad faith, and represents a kind of dishonesty to the thinking public they pretend to address.

Mysticism and Hegel’s philosophy of nature

The essay “Hegel and Mysticism” in The Cambridge Companion, by Glenn Alexander Magee, concerns itself with the mystical sources of some of Hegel’s conceptions. Perhaps more than any other, this essay expresses the retrograde intellectual trends that are aired in prominent philosophical venues without significant comment or opposition. Magee’s work is similar to that of Frances Yates and Betty Jo Teeter Dobbs, in that it attempts to reinterpret the work of a historical figure associated with the progressive development of scientific thought as an essentially religious thinker, thus attributing to religion a progressive role in historical development.

It is of course commonplace in Hegel commentaries to refer to the mysticism of his system, but as Magee points out, while this characterization may be used to evoke the obscure, confusing, or religiously inspired aspects of his thought broadly considered, it is also true that certain ideas of his find their source in religious mysticism more narrowly conceived.

Jakob Boehme

Jakob BoehmeThe most obvious influence of this sort on Hegel was the early 17th century mystic Jakob Boehme. Boehme, a “shoemaker in Goerlitz in Lusatia on the border of Bohemia,” supposedly had a vision in the year 1600, which he subsequently elaborated in a number of writings. (257) As Magee states: “Central to Boehme’s thought is a conception of God as dynamic and evolving. Rejecting the idea of a transcendent God who exists outside of creation, complete and perfect, Boehme writes instead of a God who develops Himself through creation. Shockingly, Boehme claims that apart from or prior to creation, God is not yet God. What moves God to unfold Himself is the desire to achieve self-consciousness, and the mechanism of this process was thought by Boehme to involve conflict and opposition ... The process of creation and of God’s coming to self-consciousness, eventually reaches consummation with man.” (257)

It would be difficult to dismiss the influence this idea had on Hegel. Instead of God, Hegel typically refers to the Absolute, but Hegel’s Absolute must, like Boehme’s God, come to self-consciousness in order to be the Absolute. This process occurs through the conflicts and oppositions which develop themselves through the stages, first of Logic, then of Nature, then of Spirit (human reason in history), finding full expression in the development of art, religion, and philosophy and culminating in the cognition of the Absolute in its complete development. If Magee was merely pointing out that the most openly mystical and religious aspects of Hegel’s system were borrowed from earlier writers, we could move on from this unsurprising finding without further ado.

However, Magee clearly has a more ambitious agenda in mind. In his concluding paragraph he writes: “Modern historians of philosophy naturally have viewed their subject matter through the same progressive optic, as reason asserting its autonomy and progressively dispelling the darkness of superstition. But if the very idea of the autonomy and progressive unfolding of reason has deeply irrational roots, than perhaps history is better understood as Heidegger saw it, not as an intelligible progression from superstition to reason, but merely as a random and contingent succession of superstitions, the most stubborn of which are those that present themselves as most rational.” (280)

Although Marxists reject the idealist Hegelian contention that history is the byproduct of reason unfolding itself, the great advance that Hegel represented for a scientific understanding of history was the idea of a logic to historical development, and not just a series of contingent events effected by important individuals, and punctuated by ineffable horrors. Magee not only rejects Hegel’s rational, albeit idealist, understanding of history (including the history of thought), he rejects any rational understanding of history, including a Marxist, materialist one. With this, he places himself in the camp of the postmodernists and other opponents of the Enlightenment for whom the very idea of progressive historical change is anathema and who, in the final analysis, give theoretical cover to reactionary and backward forces.

Instead of a positive characteristic of his thought, the impact of mysticism on Hegel should rather be understood in the context of the legacy of German political and economic backwardness. Although the ideas of the Enlightenment had exerted a powerful influence, Germany remained a patchwork of independent and semi-independent states under the rule of petty monarchs, each with its own laws and traditions, both secular and religious. This disunity impeded the development of bourgeois social relations and the accompanying rationalization of production on the basis of natural science, through which the latter is powerfully confirmed in practice.

Practical and scientific activity dissolves the basis upon which theory is led to mysticism, but the objective basis for this was still lacking in many respects in the Germany of the late 18th century. Hegel could still hope to mediate between the old traditions, however obscure or irrational, and the new spirit of the Enlightenment being brought into Germany, which he did precisely by bringing out the rationality implicit in the former, and arguing for their reform on the basis of the new ideas.

That Hegel could even attempt such a reconciliation is due in no small part to his excellent grasp of, respect for, and interest in the newest scientific thought and achievements, whose development he did not attempt to forestall through the use of mystical or pre-scientific ideas, although many people through the years have suspected him of attempting to do just that.

Kenneth R. Westphal’s piece in this volume dispels much of the ignorance concerning Hegel’s goals and methods in his Philosophy of Nature, the second part of his Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences. Historically, this work has often served as supposed proof of Hegel’s charlatanry as a thinker and prima facie evidence for considering all of his work highly suspect, due to its supposed a priori encroachments on the scientific process and employment of concepts such as teleology.

Most intellectual defenders of Hegel have considered the work an embarrassment, and so it has remained largely ignored even though it is vitally important to his system as a whole, providing the link between the Logic and the Philosophy of Spirit (the human-centered investigations). But the common view of Hegel as being either hopelessly clueless about science or willfully malicious is unfounded. As Westphal points out, based on recent research, Hegel was “deeply versed in the natural science of his day, as well as any nonspecialist possibly could be.” (284)

Furthermore, he “taught calculus and understood mathematics well enough to have an informed reasons for preferring French schools of analysis, particularly LaGrange’s.” (284) Newton’s theory of universal gravitation was enormously impressive to Hegel, and turns out to have been an influence on his development of dialectics, specifically in its positing of the interrelatedness of all things.

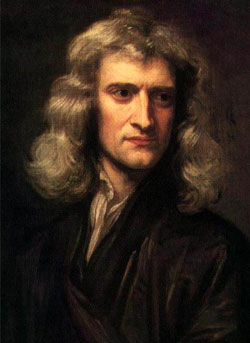

Isaac Newton

Isaac NewtonAmong the most famous of Hegel’s supposed transgressions against science is his criticism of Newton. Although long seen as a laughably misguided intervention, Edward C. Halper attempts to reconstruct Hegel’s argument and explain why it is a plausible criticism of Newton if it is correctly understood. Hegel’s criticism is based on the nature of matter assumed (but not stated explicitly) in Newton’s three laws of motion and the nature of matter implied by the theory of universal gravitation. (320)

The basic idea is that “the ‘law of inertia,’ asserts that matter in motion or matter at rest would remain so, unless acted upon by an outside body.” (320) Matter by implication is not active, but rather passive, and requires the application of force by something else for motion and change. Newton’s second and third laws carry the same assumptions. The consequence of this view is that “the entire universe requires an external agency as the source of its initial motion: hence, Newton posits God.” (322)

But this view of matter contradicts the view of matter implicit in the law of gravity. As Halper states, “According to this law, every bit of matter exerts a force of attraction toward every other bit of matter ... All matter by its nature falls, or rather propels itself toward other matter.” (322) In other words, matter, by exerting the attractive gravitational force, is active. Hegel’s resolution of this contradiction, essentially, is to propose that “inertial motion is elliptical motion around a center of gravity,” such as that manifested by the orbits of the planets in the solar system. (335) The nature of matter is to move elliptically, as suggested by Kepler, and not rectilinearly. Most interesting about the view of matter that emerges is its dialectical character. Since gravity attracts the parts of a single body towards a center by the same principle that it moves towards other bodies, its nature is thus “to move away from itself and seek to be other than itself ... matter’s inner nature is its motion toward a point outside of itself.” (334)

That Hegel would be so concerned with the findings of natural science and place the philosophy of nature as the central section of his Encyclopedia is not at all surprising. However, one cannot rely on his own explanation as to why this is so, namely that science represents a higher development of the Absolute, and thus of human reason. On the contrary, the centrality of science in Hegel’s work has a great deal to do with the powerful impetus given by the development of the forces and relations of production.

Friedrich Engels

Friedrich EngelsAs Engels quite aptly remarked, “during this long period from Descartes to Hegel and from Hobbes to Feuerbach, these philosophers were by no means impelled, as they thought they were, solely by the force of pure reason. On the contrary, what really pushed them forward most was the powerful and ever more rapidly onrushing progress of natural science and industry. Among the materialists this was plain on the surface, but the idealist systems also filled themselves more and more with a materialist content and attempted pantheistically to reconcile the antithesis between mind and matter. Thus, ultimately, the Hegelian system represents merely a materialism idealistically turned upside down in method and content.” (Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy, Ch. 02)

Conclusion

Unfortunately, there is a clear tendency in many of the contributions to view Hegel’s philosophy as suitable for the present day, without acknowledging the criticism and challenges posed by Marxism, let alone the manner in which Marxism surpassed it. Due to this rejection of the most important and profound materialist development of Hegelian philosophy, the various interpretations inevitably place more emphasis on the mystical and idealist aspects of Hegel, i.e., the backward aspects, than is warranted by Hegel’s own writings, by more or less openly drawing on Kant.

This tendency is nowhere more pronounced than among social and political philosophers, where it finds expression in the attempt to theorize a kind of “updated” liberalism—in other words, a capitalism “reconciling the best aspects of liberal social thought, including its concern for the rights and dignities of individuals, with the human need for deep and enduring communal attachments,” as Frederick Neuhouser puts it. (204)

Recognizing that capitalism is deeply corrosive to social harmony, the scholars imagine that if only the requisite social institutions were implemented along the Hegelian model, the excesses of capitalism could all be avoided through various forms of regulation, oversight, and above all, by providing the means for the moral development of citizens. This is, to put it mildly, a fantasy, and is merely a more sophisticated version of the liberal idea that the state is a neutral arbiter between classes, and that the problem with capitalism is individual capitalists, and not the profit system itself.

Although a number of essays in this collection are quite good and represent advances in Hegel scholarship, notably the essays dealing with Hegel and science, the book as a whole is profoundly flawed. Contemporary philosophy does not have the cultural resources to honestly approach these questions, and is severely hampered by widespread idealist and subjectivist outlooks and methodologies.

Follow the WSWS