Burn After Reading: Another “league of morons” from the Coen brothers

By Hiram Lee

15 October 2008

The popular filmmaking duo of Joel and Ethan Coen have followed up their bleak, Academy-award-winning No Country for Old Men with a return to comedy, the genre for which they are best known.

The writer-directors this time set out to make a spy movie or, rather, a parody of one, though it isn't exactly that either. While the work may have changed direction from its original plan, it certainly takes aim at both real-world and fictional spies. It's very far removed indeed from the sleek, romantic, super-human spy genre one sees in the Bourne trilogy or Bond films. Espionage, as portrayed by the Coens, is a mess of criminal behavior, paranoia, accidents, incompetence, bad information, "wrong men" and cover-ups.

The story concerns Osbourne Cox (John Malkovich), a disgruntled former CIA agent who has quit after his superiors demoted him because of his excessive drinking. He decides to write a memoir of his time with the agency. Through a series of unfortunate circumstances, a disc containing Osbourne's draft and other information is lost in a local gym called Hardbodies and discovered by its less-than-competent staff.

Members of the Hardbodies staff, excited by their discovery and sensing an opportunity, attempt to sell the information back to Osbourne, but soon come to understand they're in over their heads. The film is, in many ways, about spies coming into conflict with people who have seen too many of the movies that mythologize them and their underhanded practices.

Burn After Reading is often a genuinely funny film. Most amusing and memorable are the smaller, but very recognizable, things. Linda Litzke (Frances McDormand), one of the Hardbodies workers, struggles with the automated voice system of her HMO's phone service. It prompts her to answer, but doesn't understand her replies. Her anger builds as she is forced to yell and dramatically enunciate words to communicate with the machine at the other end of the line.

Another subtle but memorable moment comes in the scene where the Hardbodies workers first discover the computer disc and upload its contents to the office computer. The way Hardbodies manager Ted (Richard Jenkins) slowly backs out of the room when he sees the information speaks volumes. He's scared because he knows he's not supposed to see this, and yet he backs out slowly and with small steps so he can see as much as he can. It communicates a lot about the character with very economical means, and one feels there is also something essential about the nature of the CIA communicated in Ted's silent terror toward an innocent and accidental discovery of classified material. Ted almost instinctively fears the organization.

Moments like this happen organically as part of a larger scene. Our eye is not forced on them, we recognize them, find them on our own, and they work. It suggests, at least in the better parts of the film, that the Coens haven't wasted time trying to insert laughs but have attempted to hit on something that is comically true. It's refreshing to see at a time when film comedy is plagued with arbitrary and "random" attempts at getting laughs.

The scenes involving a divorce attorney hired by Osbourne's wife (Tilda Swinton) also ring true. The shady lawyer instructs his client to clandestinely uncover her CIA husband's finances in preparation for their divorce: "You can be a spy too, Madam." It reminds one of another of the Coens' films about divorce, Intolerable Cruelty, one of their better efforts, which was more or less ignored by critics and admirers alike.

Perhaps the very best scenes of the film occur in CIA headquarters when a superior agent (J.K. Simmons) receives reports about Osbourne's behavior and what, to him, are the completely bizarre and unintelligible activities of the Hardbodies gym staff and their efforts at blackmail. Without blinking an eye, Simmons's character orders evidence and bodies destroyed. His only task is to clean up the mess, without regard for any moral concerns, and lock all the facts away in a classified document as though the whole affair had never happened.

Other attempts by the Coens to offer insights into the CIA with more direct statements fail to come off. Osbourne, ruminating on the cause of his estrangement from the CIA, says, "Maybe it's the Cold War ending. Now it seems like it's all bureaucracy, no mission." It feels like the Coens are struggling to achieve an understanding of the CIA and certain types who work for the agency, but failing to grasp those matters.

Unfortunately, while the film has its moments, the best of them are often lost because of the Coens' recurring tendency to adopt a condescending or unnecessarily contemptuous attitude toward some of their characters.

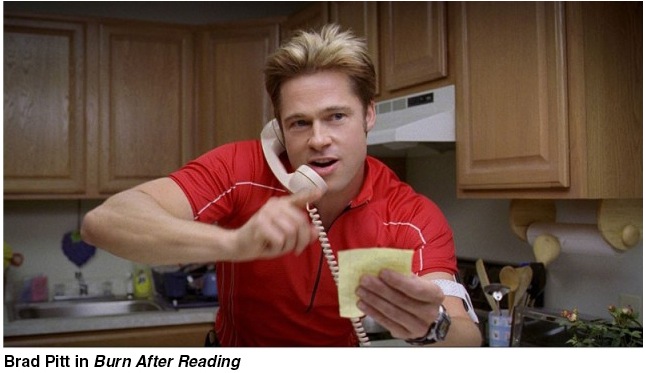

Brad Pitt plays the most absurd of the Hardbodies workers, Chad Feldheimer. There's something to Pitt's performance. His character is self-centered, though in a strangely innocent way. When he laughs, it's self-conscious and meant to be noticed. He's always performing. At times, however, Pitt is permitted to go too far with his character, pumping his fists wildly into the air and playing up as many of his characters' quirks as loudly as possible. The smaller details Pitt gives to his character work much better and are more perceptive. His character may be a half-wit, but when the Coens make him too broad and go out of their way to make him look that way, it becomes too much and perhaps a little mean-spirited.

Brad Pitt plays the most absurd of the Hardbodies workers, Chad Feldheimer. There's something to Pitt's performance. His character is self-centered, though in a strangely innocent way. When he laughs, it's self-conscious and meant to be noticed. He's always performing. At times, however, Pitt is permitted to go too far with his character, pumping his fists wildly into the air and playing up as many of his characters' quirks as loudly as possible. The smaller details Pitt gives to his character work much better and are more perceptive. His character may be a half-wit, but when the Coens make him too broad and go out of their way to make him look that way, it becomes too much and perhaps a little mean-spirited.

The handling of McDormand's character is troubling as well. The middle-aged gym employee is obsessed with plastic surgery. She wants operations on several areas of her body and pursues them with a single-minded enthusiasm. We're treated to close-ups of her skin as a doctor pokes and prods her. While her desperation for money with which to afford the operations is offered as her primary reason for her involvement in the blackmail scheme, it never truly feels like desperation. This is because both she and her operations are presented as so absurdly frivolous that viewers aren't able to care very strongly about her situation at all. Wide-eyed, with a peculiar way of speaking, McDormand is almost playing her character in Fargo, drained of sincerity.

The Coens' film too often looks down on its caricatured and insipid Hardbodies employees, and in ways it doesn't quite "look down" on Malkovich's character, or certain others. It's a recurring theme in their comedies: a group of moronic characters annoy, confuse, and make trouble for another group of characters who are more intelligent (and often ruthless). This time, the "morons" are a handful of "small potatoes," in Washington; just as often, it's a group of poor or working class rural nitwits as in Fargo or O Brother, Where Art Thou?

When Osbourne corners one of the Hardbodies employees in his basement, he could almost be speaking for the filmmakers when he tells the frightened man that he is "part of a league of morons" that the CIA agent has been opposing his whole life.

At a press conference held during this year's Toronto International Film Festival, reporters asked the Coens, in an interview published on darkhorizons.com, "This is a comic film, but there is also a very dark undertone. It seems that you walk away from it with a very pessimistic feeling about human nature. It portrays people as empty, vacuous, and self-serving. Is there really that dark undertone?"

Director Joel Coen replied, "Yeah, I'm not even sure it's an undertone. Yeah, they are pretty terrible." This is a poor place from which to begin any sort of work. Once one declares that people are "empty, vacuous and self-serving" from the start--by their very nature--it absolves the artist from having to ask very many social or historical questions. It takes its toll on the work, to say the least.

The Coen brothers are talented. They have a flair for comedy, and a unique and personal style of their own. Burn After Reading is a great deal more amusing than most American comedies released onto the screens at present. But it also suffers from some very considerable flaws that shouldn't be overlooked. Ultimately, one comes away from the work, as one does with so many of the Coens' other films, with decidedly mixed feelings.

Follow the WSWS