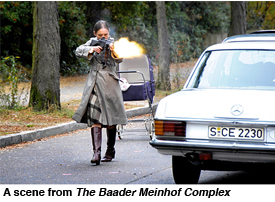

The Baader Meinhof Complex

A superficial treatment of the history of the Red Army Faction

By Peter Schwarz

30 October 2008

Directed by Uli Edel, screenplay by Edel and Bernd Eichinger, based on the book by Stefan Aust

Three decades after the "German autumn"—the climax of a wave of bomb attacks and kidnappings by the Red Army Faction (RAF)—producer and writer Bernd Eichinger (Downfall, Perfume: The Story of a Murderer) has brought the history of this terrorist group to the screen.

The film begins in 1967. Klaus Rainer Röhl, publisher of the radical magazine Konkret, his wife Ulrike Meinhof (Martina Gedeck) and his two small daughters spend their summer vacation in blissful nakedness on a nudist beach on the North Sea island of Sylt. On the front page of an illustrated magazine can be seen the picture of the Shah of Iran and his wife Farah Diba. Röhl explains to his daughters—against the protests of Meinhof—that the Shah tortures his opponents and cuts off their heads.

The film begins in 1967. Klaus Rainer Röhl, publisher of the radical magazine Konkret, his wife Ulrike Meinhof (Martina Gedeck) and his two small daughters spend their summer vacation in blissful nakedness on a nudist beach on the North Sea island of Sylt. On the front page of an illustrated magazine can be seen the picture of the Shah of Iran and his wife Farah Diba. Röhl explains to his daughters—against the protests of Meinhof—that the Shah tortures his opponents and cuts off their heads.

The next scene shows the anti-Shah demonstration of June 2. The Shah and his wife are arriving at the German Opera in Berlin. On the other side of the street—behind a dense police cordon—demonstrators wave banners and chant slogans. Between the police and the visiting Iranian monarch are his supporters—a group of well-trained brawny men in black suits—waving pro-Shah posters.

Suddenly, the Shah supporters cross the police line and begin to viciously beat up the peaceful demonstrators. A woman is bleeding. The police stand by, doing nothing. Finally, they pull out their truncheons and brutally drive apart the demonstrators. One sees the disbelieving, frightened and indignant faces. A shot rings out in a courtyard. The police officer Karl-Heinz Kurras has shot the student Benno Ohnesorg.

Now the events fast forward. In a Berlin apartment, the first bombs are being made. Rudi Dutschke addresses the Berlin congress against the Vietnam War and is shot down on the street. Andreas Baader (Moritz Bleibtreu) and Gudrun Ensslin (Johanna Wokalek) set fire to a Frankfurt department store. They are arrested. Ulrike Meinhof takes part in their liberation. A person is seriously injured (accidentally) and the group submerges into the underground.

Trained by Fatah forces in Jordan in bank robberies and bombings, the arrested RAF members are kept in solitary confinement as a group in the high security wing of Stammheim prison. On television, radio and in secret messages, they follow how the second generation takes over the command and the terror escalates: cold-blooded attacks on prominent representatives of the state and big business, hostage-taking in the German embassy in Stockholm, and finally—in the "German autumn" of 1977—the abduction of Hans Martin Schleyer (Bernd Stegemann), president of the German Employers Association, as well as the hijacking of a Lufthansa plane by a Palestinian commando unit. The object of both actions is to secure the release of the prisoners in Stammheim.

Ulrike Meinhof is already dead by this time, found hanged in her prison cell. Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin and Jan-Carl Raspe are likewise found dead in their cells on the morning of October 18. Previously, a "special forces" operation had overwhelmed the hijackers in Somalia. The film ends with the execution of Schleyer, who is shot in the head.

The Baader Meinhof Complex certainly has some positive aspects.

This is largely due to the outstanding cast. Eichinger has engaged some of the best representatives of the current generation of actors, who strive to create a nuanced portrayal of their characters. Above all, the scenes in Stammheim are played outstandingly. The main participants have walled themselves into a political dead end. They suffer the consequences of solitary confinement, argue bitterly with each other, their personalities disintegrate; they rebel desperately against their situation, and are monitored and watched round the clock.

A further plus is the care and attention to detail with which the historical events are reconstructed. The production invested much effort and money to this end. The film was largely filmed at the original locations and received subsidies of €6.5 million.

Nevertheless, the film remains essentially superficial and flat. There has been an obvious endeavour not to cause offence in any quarter. It provides an uncritical, conventional view of the events and avoids any awkward questions.

Eichinger and Stefan Aust, the long-standing editor-in-chief of newsweekly Der Spiegel, on whose eponymous book the film is based, clearly did not want to come into conflict with the leading circles in politics and the media. While they have resisted the temptation to portray the Baader Meinhof group as a non-political, purely criminal gang, as those in leading Christian Democrat and Social Democrat circles still do, what is offered to illuminate the social and political context does not go beyond hollow clichés.

Some critics have attributed this to the fact that the film attempts to condense the events of 10 years into two-and-a-half hours of screen time, succumbing to the temptation to give action scenes more emphasis. According to such views, the film depends on action and visual effects and is little suited for critical reflection. But this is too simple an account. Der Baader Meinhof Komplex is not only an action film. The script provides considerable space for background material and dialogue, but this material is carefully filtered. Some aspects are downplayed, and others are consciously excluded.

What should the audience make of this film? Why did women such as Ulrike Meinhof and Gudrun Ensslin, who both originally aspired to high moral values in their politics, end up in the reactionary dead-end of individual terrorism?

What should the audience make of this film? Why did women such as Ulrike Meinhof and Gudrun Ensslin, who both originally aspired to high moral values in their politics, end up in the reactionary dead-end of individual terrorism?

The film offers little basis to clarify these questions. A filmgoer—born in the 1970s or 1980s—would find it simply incomprehensible that while the 1968 protest movement attracted hundreds of thousands, why then did a small group slide into terrorism? A little free love and a little anarchy (Baader races along the streets in stolen cars), combined with abstract, hollow clichés about imperialism and freedom are all the film has to offer as explanation.

Is one to conclude from Der Baader Meinhof Komplex that all protest against the ruling order leads to an orgy of violence and that it is better to avoid it altogether? The film does not go quite this far, but it certainly does not exclude such a conclusion.

Amongst the best scenes is certainly the one initially described—the demonstration against the Shah's visit—as well as brutal original film material documenting the Vietnam War. They serve to explain the anger and rage felt by many young people at that time. But the film does not go any further. The disproportionate way in which the state and media react to the student protests and the initial actions by Baader and Ensslin, find hardly any expression in the film.

This was even noticeable to Gerhart Baum (Free Democratic Party), who from 1972 to 1978 was an undersecretary in the interior ministry and from 1978 to 1982, interior minister with overall responsibility for the state's apparatus of suppression. In a recent edition of Die Zeit, he writes of The Baader Meinhof Complex: "Unfortunately, important circumstances are omitted—such as the public panic and hysteria fomented by the media and politics... also omitted is the exploitation of the terror for political ends, by which the constitutional state placed itself in danger. Occasionally, the state showed the ugly face that its opponents wanted to depict. It would have been good, if the film had dealt with the theme of the constitutional state, which became unhinged in a state of emergency and fear."

This, according to Baum, is still an important topic today: "Our fundamental rights are being damaged in the fight against terror—then as now."

The film also completely omits any reference to Germany's Nazi past—the fact that in the post-war period, state personnel, judges and professors, were able to move smoothly from the Third Reich into new posts; that hardly anyone was brought to account for the crimes of the Nazis. Nor does it address the Emergency Laws enacted under the Christian Democrat-Social Democrat grand coalition in 1968. Both contributed just as much to the emergence of the mass student protest movement as the Vietnam War and the anti-Shah demonstrations.

What weighs far more heavily, however, is the complete exclusion of the role of Stalinism and social democracy. There really can be no innocent explanation for this; the film clearly comes to the defence of both.

Without a historical knowledge of the period, most cinema-goers would simply not know that Konkret, for which Ulrike Meinhof wrote, was originally backed by the illegal German Communist Party and the Stalinist regime in East Germany. The film also gives no indication of the fact that in 1967 the Social Democratic Party (SPD) was responsible for the activities of the police in Berlin, nor that since 1966 the SPD had participated in a federal coalition government led by Kurt Georg Kiesinger (Christian Democratic Union), a former member of Hitler's Nazi party.

The reactionary role of Stalinism and social democracy contributed significantly to the mixture of indignation and impotence that drove Meinhof, Ensslin and others into the dead end of terrorism. The crimes of Stalinism, which culminated in the summer of 1968 in the suppression of the Prague spring in Czechoslovakia, cut off the students' justified indignation from a socialist perspective. And the SPD unreservedly supported the Emergency Laws and the stepping up of state powers against the student protests.

A section of the student left ascribed responsibility for the policies of the SPD to the workers, who had voted for the SPD by a large majority. Basing themselves on the theories of the Frankfurt School, and in particular Herbert Marcuse, they regarded the working class as a reactionary mass, which consumerism had completely integrated into the capitalist system. From this they concluded that only individual "revolutionary action" could electrify social consciousness—a theory that found its ultimate murderous consequences in the terrorism of the RAF.

These connections are not made clear in the film. The appeals written by Ulrike Meinhof, which are repeatedly cited in the film, and the speech given by student leader Rudi Dutschke, are reduced to just a few sound bites, which make hardly any sense to a contemporary audience. The great struggles of the working class, which began with the French general strike in May 1968 and then rolled across Europe until 1975, are ignored—although they refuted the theories of Marcuse and undermined the theoretical stance of the RAF, which confused individual acts of terrorism with revolutionary politics.

The film's authors obviously felt that they needed some social explanation for the phenomenon of the RAF. Therefore they invented an artificial character. While all the other roles are played by actors who are as similar in age and appearance as possible to the real person they portray, Horst Herold, who in 1971 at the age of 48 took over the Federal Criminal Investigation Office, is played by the 67-year old Bruno Ganz (Hitler in Downfall). Ganz plays the part as the wise old police commissioner, who sits reflecting at his desk and expounds to his fellow workers how terrorism has social causes and can only be eliminated through the eradication of poverty in the Third World. But this artifice cannot hide the film's fundamental weaknesses.

Follow the WSWS