Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima: Remarkable, in many ways

By David Walsh

6 February 2007

Letters from Iwo Jima, directed by Clint Eastwood, screenplay by Iris Yamashita

Clint Eastwood’s Letters from Iwo Jima is, in many ways, an unusual and remarkable work. The director, after representing, in Flags of Our Fathers, the American side of the World War II battle for the Japanese island of Iwo Jima and its later consequences for a number of soldiers, has turned his attention to the fate of the Japanese troops.

In the conflict, which raged for more than a month in February and March 1945, 100,000 US troops attempted to root out 22,000 defenders. Nearly 7,000 American forces died (and some 19,000 were wounded) on Iwo Jima; only 1,100 or so Japanese survived.

As a framing device, Eastwood stages the digging up of a batch of letters on Iwo Jima in 2005. Throughout the film we hear passages from letters written by Lt. General Tadamichi Kuribayashi (Ken Watanabe), as well as a more humble soldier, the baker Saigo (Kazunari Ninomiya).

Kuribayashi was placed in charge of Iwo Jima’s defenses in the summer of 1944. The film begins with his arrival on the island. Saigo and his comrades are slogging away, digging trenches on the beach. The new commander puts an end to that, and insists instead on building defenses in the island’s mountains. In the end, the Japanese built an elaborate network of 5,000 caves, tunnels and pillboxes, approximately 18 miles long. Some of the manmade caverns could hold as many as 300 to 400 people.

Eastwood’s film portrays Kuribayashi as a cosmopolitan figure. Of samurai descent and an aristocrat, the Japanese officer had been partially educated in Canada and lived for two years in the US, serving as a deputy military attaché. He was reportedly opposed to a Japanese war with America, impressed as he was in particular by the latter’s industrial capacity.

Kuribayashi realized that his forces would not be able to hold out in the end against a massive invasion force. The Japanese high command was not able to provide him with any air or naval support. His aim became to make the taking of Iwo Jima as costly as possible for the Americans. “Do not expect to return home alive,” he tells his men. Opposed to ritual suicide and the equally suicidal and bloodcurdling “banzai charge,” which alerted the enemy to one’s presence, Kuribayashi insisted that no soldier could die before killing 10 from the other side.

The script, by Iris Yamashita, places a good deal of emphasis on the division between the worldly Kuribayashi and Baron Nishi (Tsuyoshi Ihara), an equestrian Olympic champion in the 1932 Games, on the one hand, and a group of militarist zealots among the Japanese officer corps, on the other, including the fanatical Lieutenant Ito (Shido Nakamura). The latter, religiously devoted to Emperor and the homeland, is almost eager to die by his own hands and to see his men suffer the same fate. (As the battle inevitably goes badly for the Japanese, a mass suicide by hand grenade is one of the ghastly fruits of this kind of effort.) These other officers conspire against Kuribayashi from the start, opposing his defensive strategy as well as his leniency toward the rank-and-file soldiers.

How much of this conflict is based in fact and how much results from the filmmakers’ perceived need to create dramatic tension and, moreover, offer a more sympathetic Japanese commander is unclear. Kuribayashi clearly had tactical differences with the general staff, but he was also one of the few Japanese officers to be granted a personal audience with Emperor Hirohito and was assigned to the defense of Iwo Jima by Prime Minister Hideki Tojo.

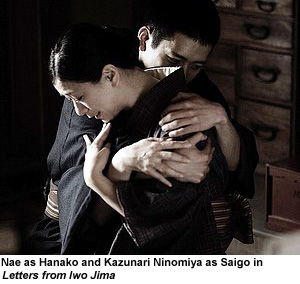

In any event, Ninomiya’s Saigo provides much of the film’s emotional and social strength. From the beginning, when he gets into trouble for unpatriotic remarks while digging trenches in the sand (“Damn this island, the Americans can have it!”), he moves us and holds our interest. In flashbacks, we see him and his young wife Hanako (Nae) trying to make a go of their bakery, which is ruined by the war. One evening, a knock at the door leads to the unwelcome news that Saigo has been drafted. A neighbor tells Hanako, “Congratulations! Your husband is going to war.” The faces of the young couple tell a very different story. Later she cries out to him, “None of the men ever return.”

Another intriguing flashback involves Shimizu (Ryo Kase), a new member of Saigo’s unit on Iwo Jima. When he tells his new comrades that he was trained at the Imperial Japanese Academy, Saigo assumes that he is a member of the Kempeitai, the notorious military and secret police, sent to spy on them. (The Kempeitai played a brutal role in Korea in particular, under Japanese colonial rule, and also persecuted left-wing and anti-war forces at home. It often carried out arrests without a warrant and resorted to torture.)

In fact, we learn later that Shimizu has been tossed off that force after only a few days, for showing humanity. While on patrol, Shimizu and his Kempeitai commander come across a house not displaying the Japanese flag. A woman, whose husband is at war, lives there and is unable to put up the flag by herself. Shimizu helps her, but during the process the family dog barks at him. His superior orders him to shoot the dog for disrupting “military communications.” Shimizu only pretends to kill the animal, but the ploy is revealed and his commander beats him, calling him a weakling.

The letters from the Japanese soldiers, almost all of them fated to die on the island, concern themselves with the mundane details of life. Kuribayashi apologizes to his wife for leaving before he could finish the kitchen floor. Saigo longs to see the baby daughter born after his departure. Later, Nishi reads a letter found on a dead American soldier, from his mother, telling him about a dog that dug a hole under a fence and ran off and other everyday events. She adds, ‘Please come home safely.’ These moments are affecting and underscore the horror of war, its terrible waste.

Ninomiya as Saigo is especially appealing. The performer, a pop music star and television and stage performer in Japan, has a deeply human face. His Saigo is one of those individuals who will never boss others around, although he experiences a good deal of it himself. While at work on the beach making trenches, he writes his wife, “Am I digging my own grave?”

Ninomiya explains, “I play an ordinary baker who is thrown into a situation that forces him to lose his humanity in order to survive.... The war is so cruel that it leaves nothing behind, and the scars of war can never fade.”

One must give Eastwood a good deal of credit for making Letters from Iwo Jima. To make a film about the suffering “your” soldiers endure is one thing, to make one about the horrors inflicted on the “enemy” is something else again. There is a certain significance about this work being made in the midst of the Bush administration’s endless “war on terror,” which consumes countless lives and billions of dollars. American filmmaking has come some distance at least since Saving Private Ryan in 1998.

According to the “principle of counterpoint,” perhaps only an Eastwood, rightly or wrongly associated in the past with a patriotic and “law-and-order” outlook, could have gotten away with this film. Nevertheless, it took a certain amount of courage.

He says, “In most war pictures I grew up with, there were good guys and bad guys. Life is not like that and war is not like that. These movies [Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima] are not about winning or losing. They are about this war’s effects on human beings and those who lose their lives much before their time.”

The director explains that research brought the Japanese soldiers to life. “The young conscriptees that were on the island were very much like the Americans. They didn’t necessarily want to be in the war. They were sent there and told not to plan on coming back. This is something you could not tell an American with a straight face. Most people go into combat thinking, ‘Yes, it could be dangerous and I could get killed, but I could also make it home and get back to normal.’

“There was a great probability at the time that they would remain there on the island. This is a mentality that is very hard for me personally to understand. But to try to understand that, I read as much about them and what it was like for them as I could.”

Actor Ken Watanabe comments, “We can understand somewhere in the back of our minds that war is not good, but it is rather seldom that we hate war from the bottom of our hearts in daily life. When you see what was done there, the reality of it, you will never wish to send your sons or sweethearts to war.”

Speaking of World War II, Eastwood (born in 1930 in San Francisco) who was a teenager when it ended, remarks, “I remember that I was pleased it was over. Everybody around the world was yearning for a peaceful state. I just hope we all have many peaceful states in our lifetime...all of us.”

Shot in 32 days for $20 million, a pittance these days, Letters from Iwo Jima has its weaknesses. A film often goes on too long, as this one does, because the filmmaker is not certain of his or her theme. Eastwood cannot jump out of his skin. Saigo’s fate in particular is drawn out, presumably to demonstrate once again that from the director’s standpoint the embattled individual is entitled to do anything in his or her power to survive. This relentless individualism took a rancid form in Million Dollar Baby, which argued that as long as he pulled a long face after the fact, the Eastwood character was permitted to commit any number of crimes.

The absence of the Eastwood persona, which no doubt carries with it a certain amount of ideological and quasi-mythic baggage, may help in Letters from Iwo Jima. Here is something more lifelike and genuinely tragic for a change.

Follow the WSWS