Now available from Mehring Books: Russian Revolutionary Posters by David King

By David Walsh

29 November 2012

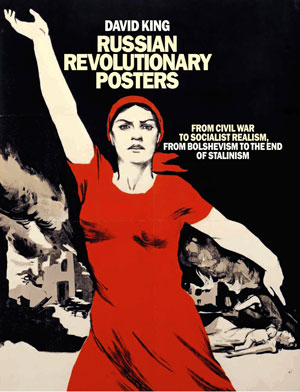

Mehring Books is proud to offer for sale a new book, Russian Revolutionary Posters: From Civil War to Socialist Realism, From Bolshevism to the End of Stalinism by David King (Tate Publishing).

Mehring Books is proud to offer for sale a new book, Russian Revolutionary Posters: From Civil War to Socialist Realism, From Bolshevism to the End of Stalinism by David King (Tate Publishing).

The volume contains images and descriptions of 150 political and cultural posters, drawn from the David King Collection at the Tate Modern in London, Britain's national gallery of international modern art.

The list of works to which King—artist, designer, editor, researcher, photohistorian and archivist—has contributed as either designer or author, or both, is extraordinary, including Trotsky: A Documentary (1972), Alexander Rodchenko (1979), Trotsky: A Photographic Biography (1986), The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin's Russia (1997), Ordinary Citizens: The Victims of Stalin (2003) and Red Star Over Russia: A Visual History of the Soviet Union from the Revolution to the Death of Stalin (2009).

As King noted in a 2008 interview, revealing the truth about the history of the Russian Revolution, Trotsky’s role and the rise of Stalinism “took on a life of its own” for the artist-editor more than forty years ago. “It became an all-consuming passion. It ran my life. Uncovering this history continues to run my life.”

As King noted in a 2008 interview, revealing the truth about the history of the Russian Revolution, Trotsky’s role and the rise of Stalinism “took on a life of its own” for the artist-editor more than forty years ago. “It became an all-consuming passion. It ran my life. Uncovering this history continues to run my life.”

Russian Revolutionary Posters is part of this life-long effort. Many of the images in the new book are breathtaking, but King’s texts considerably add to them. In his introduction, the author-editor notes, “From 1918 to 1921 over two hundred poster artists and designers sympathetic to socialism created an avalanche of political posters, widely considered to be the greatest in history, in defence of the Bolshevik Revolution.”

He explains entertainingly how he tracked down a unique and prized work, The Russian Revolutionary Poster, written and edited by Vyacheslav Polonsky (1925), “a large format Russian album … full of colour reproductions of political posters and photographs of agitational propaganda trains.”

King proceeds to explain something about Polonsky, one of the remarkable generation of Russian socialists and “the Bolsheviks’ creative director.” A man who praised Trotsky’s Literature and Revolution and whose authoritative book on revolutionary posters did not include a single image of Stalin, Polonsky was silenced after Trotsky was sent into exile, accused of “counter-revolutionary activities.” He died of typhus in 1932.

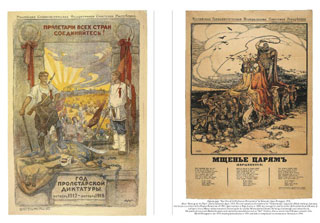

King also discusses several of the artists whose posters, in some cases, are iconic. Dmitrii Moor, for example, painted fifty revolutionary posters in 1919 and 1920, including the famed “Death to World Imperialism” (included in the book), which is staged, King observes, “as if it were the grand finale of some fabulous opera.”

King also discusses several of the artists whose posters, in some cases, are iconic. Dmitrii Moor, for example, painted fifty revolutionary posters in 1919 and 1920, including the famed “Death to World Imperialism” (included in the book), which is staged, King observes, “as if it were the grand finale of some fabulous opera.”

Another deserving figure King discusses is the artist known as Deni, prone to hypochondria and melancholy, who also produced some fifty revolutionary posters during the civil war: “Some of them,” he writes, “once seen are never to be forgotten, like ‘Capital’ and ‘A Pig Trained in Paris’” (also included in the present volume).

There are too many images in the new book to be discussed here, including a reproduction of El Lissitsky’s magnificent 1920 poster, “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge.” The commitment and passion of the artists, inspired by the October Revolution and the cause of world socialism, comes through on every page.

King’s book also traces out the degeneration of the Soviet Union under Stalinism as this found expression in poster imagery. First, in the mid-1920s, came the “cult of Lenin,” a trend that Lenin, who died in 1924 and “disliked any form of adulation,” would have despised. This was followed in the 1930s, as King writes, “by the much more fearsome Stalin Cult, also engineered by Stalin.”

Ironically, the “greatest exponent of the Stalin Cult was undoubtedly Gustav Klutsis, an artist turned poster designer who did so much to visually mythologise Stalin. The dictator later had him shot.” Numerous examples of Klutsis’s work are to be found in the new book.

Ironically, the “greatest exponent of the Stalin Cult was undoubtedly Gustav Klutsis, an artist turned poster designer who did so much to visually mythologise Stalin. The dictator later had him shot.” Numerous examples of Klutsis’s work are to be found in the new book.

In addition to his introductory remarks, King offers insightful descriptions and comments on each of the images, which are often miniature essays. For example: “‘Be on Guard!’ by Dmitrii Moor with text by Trotsky, published during the Russo-Polish War [1920]. A soldier of the Red Cavalry stamps on the Polish landlords while capitalists from Finland, Estonia, Latvia and Romania hover around hoping to become a potential threat. … Trotsky advised Lenin that the Red Army’s counter-attack should stop at the Polish border. Lenin disagreed, believing a Soviet Poland was in his sights. It wasn’t to be.”

The posters also exhort the population about cultural and hygienic questions. Over an image of a book held open by a hand grasping a peasant’s scythe, one 1920 poster reads in part, “To Produce More, You Must Know More.”

Some of the most moving posters appeal to oppressed layers of the Soviet population, women workers and peasants, the peoples of the East. In a 1921 poster by Nikolai Kochergin, in the Tatar language, King remarks, “Muslim women hail the arrival of their Russian sisters who are offering them liberation through literacy, politics and rolled-up sleeves.”

All in all, this is an indispensable work.

***

Russian Revolutionary Posters

David King

Tate Publishing (September 1, 2012)

Special Sale Price: $34.95 from Mehring Books

Product Dimensions: 12.7 x 10 x 0.8 inches

Shipping Weight: 2.6 pounds

To order, click here.

Follow the WSWS