Jack London’s The Iron Heel: An enduring classic

By Jack Hood

8 March 2012

“I am deep in the beginning of a socialistic novel … I am going to call it The Iron Heel. How’s that for a title? The poor futile little capitalist! Gee, when the proletariat cleans up some day!” The excitement of this letter to a friend underscores the enthusiasm that animated the work of John Griffith Chaney, a.k.a. Jack London (1876-1916), while writing his first explicitly political novel, The Iron Heel, first published by Macmillan in 1908.

“I am deep in the beginning of a socialistic novel … I am going to call it The Iron Heel. How’s that for a title? The poor futile little capitalist! Gee, when the proletariat cleans up some day!” The excitement of this letter to a friend underscores the enthusiasm that animated the work of John Griffith Chaney, a.k.a. Jack London (1876-1916), while writing his first explicitly political novel, The Iron Heel, first published by Macmillan in 1908.

The work, set in the future and covering in detail the years 1912 to 1932, envisions a defeated working class uprising and the rise of an oligarchic dictatorship in the US, followed centuries later by a social revolution.

The prescience of the novel is remarkable. In a letter written to London’s daughter Joan three decades after the book’s publication, in 1937, Leon Trotsky noted that the author “not only absorbed creatively the impetus given by the first Russian Revolution [of 1905] but also courageously thought over again in its light the fate of capitalist society as a whole … Jack London felt with an intrepidity which forces one to ask himself again and again with astonishment: when was this written? Really before the [first world] war?”

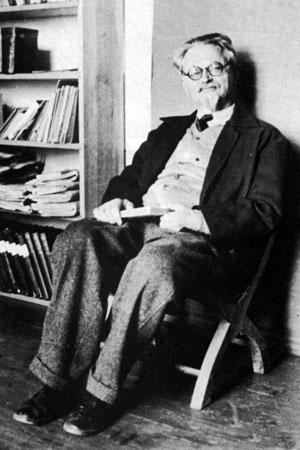

Leon Trotsky in Mexico

Leon Trotsky in MexicoIn particular, Trotsky was struck by London’s appraisal of the trade union bureaucracy and the counter-revolutionary role it would play in his imagined events. In his understanding of the labor aristocracy’s “treacherous role,” Trotsky suggests, London was far in advance of “all the social democratic leaders of the time taken together.” Beyond that, however, Trotsky adds, at the time of the novel’s writing, “not one of the revolutionary Marxists, not excluding Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg, imagined so fully the ominous perspective of the alliance between finance capital and labor aristocracy. This suffices in itself to determine the specific weight of the novel.”

(There is a further London-Trotsky connection. London co-wrote one of his early works, an epistolary novel, The Kempton-Wace Letters (1903), with Anna Strunsky, a lifelong socialist and author. Her sister, Rose Strunsky, also a socialist, would translate Trotsky’s Literature and Revolution into English in 1925, the translation still in general use.)

The Iron Heel’s insights and strengths are inseparable from its author’s social outlook and experience. London joined the Socialist Labor Party led by Daniel De Leon in April 1896. That year, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a story about him giving nightly speeches in Oakland’s City Hall Park for which he was later arrested. In 1901, he left the Socialist Labor Party to join the new Socialist Party of America. He ran as a Socialist candidate for mayor of Oakland in 1901 and later toured the country lecturing on socialism in 1906.

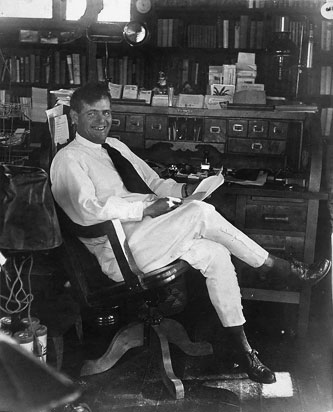

Jack London in 1916

Jack London in 1916In an essay written in 1910, London recounted mass meetings held and donations sent in support of the Russian Revolution of 1905. A passage from the essay gives one an impression of the revolutionary movement London identified with and often channeled in his writing.

Citing the millions around the world who at the time “began their letters ‘Dear Comrade,’” London marveled at what the future held, “Here are 7,000,000 comrades in an organized, international, world-wide, revolutionary movement. Here is a tremendous human force. It must be reckoned with. Here is power. And here is romance—romance so colossal that it seems to be beyond the ken of ordinary mortals. These revolutionists are swayed by great passion. They have a keen sense of personal right, much of reverence for humanity, but little reverence, if any at all, for the rule of the dead. They intend to destroy bourgeois society with most of its sweet ideals and dear moralities, and chiefest among these are those that group themselves under such heads as private ownership of capital, survival of the fittest, and patriotism—even patriotism.”

London was not untouched by the social and ideological contradictions of the early socialist movement in the US, and the working class itself. He was, for example, alternately fascinated and repelled by the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche and his theory of the “superman.” However, the sincerity of London’s early socialist convictions is unchallengeable.

The Iron Heel predicts the rise of fascism emerging from a rotting capitalism, and the terrible implications of that for the working class and its leadership. The novel traces the rise of ruling class political organizations controlled by “The Plutocracy” or “The Oligarchy,” combined into a single entity that London vividly dubs “The Iron Heel,” whose brutality is detailed throughout the novel.

The story is written in a complex and unique way: The novel takes the form of a manuscript, originally composed by Avis Everhard, the lover and political confidant of Ernest Everhard, a leader of what is referred to as the “2nd Revolution” of 1912-32. This manuscript is discovered and edited by a fictitious historian, Anthony Meredith, who supposedly recovers the manuscript in the 26th century, after the Oligarchs have been routed and are followed by a period of socialist tranquility, economic affluence and equality presided over by what is referred to as “The Brotherhood of Man.”

To understand the social genesis of The Iron Heel, it is necessary to take some account of the decade preceding the First World War. Social, economic and military tensions then building on a national and international level find expression in London’s story.

1905 and 1906—years immediately preceding the publication of The Iron Heel—saw a series of international events that deeply influenced London’s understanding of capitalist society and the struggles that would flow from its decay. War between Russia and Japan in 1904-05 left hundreds of thousands dead, leading to the 1905 Russian revolution, the “dress rehearsal” for the October Revolution twelve years later.

The US, the newest imperialist power, was fresh from its colonial subjugation of Cuba and the Philippines, the latter conflict resulting in the deaths of as many as one million Filipinos.

During this period, membership in the Socialist Party of the US rose to 135,000 and various Socialists began to gain prominence, with members elected to public office across the United States. Eugene Debs, as candidate for President in 1904, received a total of 402,810 votes—enough for third place overall. Ruling classes over the world responded with an intensified crackdown on workers’ organizations and revolutionary parties, throwing out elementary democratic rights. The anger and anxiety felt by wide layers of American workers reflected itself in the pages of The Iron Heel as they turned to socialism in great numbers.

Perhaps the most interesting theme in The Iron Heel, however, is the importance of international solidarity among the workers in their opposition to the Oligarchs and their exploitative schemes. In a chapter called “The General Strike,” London outlines how the contradictions between capitalism and national boundaries make inevitable the constant threat of imperialist war:

“The hard times at home had caused an immense decrease in consumption. Labor, out of work, had no wages with which to buy. The result was that the Plutocracy found a greater surplus than ever on its hands. This surplus it was compelled to dispose of abroad, and, what of its colossal plans, it needed money. Because of its strenuous efforts to dispose of the surplus in the world market, the Plutocracy clashed with Germany. Economic clashes were usually succeeded by wars, and this particular clash was no exception. The great German war-lord prepared, and so did the United States prepare.

“The war-cloud hovered dark and ominous. The stage was set for a world-catastrophe, for in all the world were hard times, labor troubles, perishing middle classes, armies of unemployed, clashes of economic interests in the world-markets, and mutterings and rumblings of the socialist revolution.”

However, disaster is averted through socialist internationalism, expressed in the story as the General Strike of 1912. After a confrontation between the armed forces of Germany and the United States and a series of declarations of war that closely mirror the battle-lines drawn in 1914, the working classes of Germany and the United States coordinate and successfully organize a work stoppage that results in the ruling classes of all involved nations effectively calling off the war.

In the novel, the ruling classes of both countries strike back against the workers’ successful disruption of war with increased bitterness. Martial law, concentration camps and illegal assassinations follow. London explains how an anti-democratic re-writing of the United States constitution is carried out by the fascist government after the book’s hero, Ernest Everhard, is framed in a bombing of Congress that resembles the Reichstag fire and frame-up of 1933.

Significantly, the novel also illustrates the futility and danger of reformist politics by drawing out the connection between reformism, the selling-out of the workers’ movement and its ultimate crushing under the “Iron Heel” of fascism. London hoped that the book would serve as a lesson to the working class about the importance of revolutionary leadership in the struggle for power.

As economic and social conditions radicalize workers today in ways that often parallel the period of social upheaval of the early 20th century, Jack London’s novel retains considerable power and relevance.

Note: In another recent austerity measure, Democratic Governor Jerry Brown and a Democratic-controlled state legislature voted to close the Jack London State Park, in Glen Ellen, California last year. The gates were locked in September 2011.

Follow the WSWS