The Crucible: Arthur Miller’s classic still scalds

By Richard Adams

29 June 2012

A Dollar Bill Production, produced by Sean Thomas, directed by Bill Voorhees, at the Lillian Theatre in Hollywood, California, June 15-July 14, 2012.

Trevor H. Olsen as "Reverend Parris", Bernadette Speakes as "Tituba", Anthony Backman as "Reverend John Hale", and Doug Burch as "Giles Corey" [Photo Credit- Sean Thomas]

Trevor H. Olsen as "Reverend Parris", Bernadette Speakes as "Tituba", Anthony Backman as "Reverend John Hale", and Doug Burch as "Giles Corey" [Photo Credit- Sean Thomas]Ever since American playwright Arthur Miller’s The Crucible premiered on Broadway in 1953, the play has been seen as a parable for the political witch-hunts of the McCarthyite era. Miller used the religious hysteria of the witch trials that convulsed the town of Salem, Massachusetts in the 1690s to throw light on the infamous hearings conducted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and related events in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Miller wrote his play at the height of the Red Scare just as the Hollywood blacklist was tearing apart the lives of many of his colleagues and peers. State Department official Alger Hiss had just been convicted of perjury, and physicist Klaus Fuchs of the Manhattan Project and Ethel and Julius Rosenberg convicted of espionage. Fuchs was sentenced to fourteen years in prison; horrifyingly, the Rosenbergs would be executed on June 19, 1953. The Crucible opened in January 1953.

As a result of these state-sponsored purges, hundreds of U.S. citizens were imprisoned and over ten thousand lost their jobs. McCarthyism and its enduring impact have been examined in greater depth elsewhere in these pages, but to put this play in some context, it is worth remembering that the Hollywood studios instituted the blacklist against suspected Communists in November 1947. (The anti-communist purge of the American film industry)

Eventually, the film industry blacklist included some three hundred screenwriters, directors, actors and composers (named in publications such as the pamphlet “Red Channels”), their careers curtailed or ended outright. The abject capitulation of the entertainment industry took its toll on the lives and careers of such notables as Edward G. Robinson, Paul Robeson, Lillian Hellman, Charlie Chaplin, Aaron Copland, Dashiell Hammett, John Garfield, Ruth Gordon, Edward Dmytryk and Miller himself.

Out of this cauldron of intimidation, cowardice and betrayal came The Crucible.

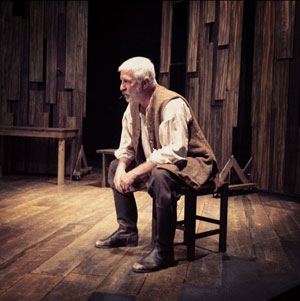

Doug Burch as Giles Corey in The Crucible

Doug Burch as Giles Corey in The Crucible[Photo Credit – Sean Thomas]

While Miller’s characters share names with historical figures in Salem in 1692-93, many are composites. And while he based his narrative on the actual events, in which some twenty innocent people were eventually executed for witchcraft, the dramatist took liberties with the ages and number of people swept up in what has come to be called the Salem witch trials.

There are different theories about what really happened in Salem in the last decades of the seventeenth century. One compelling explanation sees the trials as the culmination of disputes over property lines in a far-flung community still wresting control of land and woodlots from the surrounding forest and native population. Salem was a particularly litigious place with many documented instances of suits for libel and slander, typically among neighbors arguing over land ownership.

Another theory views the trials as an expression of tensions between town and country, between those seeking to establish communities that aped British models, but whose religious norms would be enforced by theocratic rule, a Calvinist Geneva in the American wilderness.

Yet another sees the Salem trials as a public battle between theological factions that were ripping apart the local congregations. Still another sees it as a form of religious revivalism, a precursor of the First Great Awakening typically identified with Jonathan Edwards, as the third generation of New Englanders sought to address the lapsing of religious fervor and commitment to rigorous Puritan mores. A corollary to this theory claims that the trials were an exercise in self-definition as ties to the settlers’ native England became ever more attenuated after the end of the Cromwellian era and the restoration of a king with Catholic sympathies.

For those who know this history, Miller’s play is extremely rich in subtext. Each and every one of those theories finds some expression in a narrative detail of the script, an element of character or pivotal reference. While Miller was not attempting to write a history play as such, much less deliver a lecture, he had clearly done his homework, and his incorporation of historical, economic and class conditions in the world of his play enrich it far beyond the easy and often clichéd labeling of The Crucible as merely a parable about McCarthyism.

Bill Voorhees as "John Proctor" and Jessicah Neufeld as "Abigail Williams" [Photo Credit- Sean Thomas]

Bill Voorhees as "John Proctor" and Jessicah Neufeld as "Abigail Williams" [Photo Credit- Sean Thomas]Bill Voorhees, who directed, produced and stars as John Proctor—a farmer and the play’s protagonist—in this production, was hampered, I suspect, by having worn too many hats. Certain scenes, however, especially the big courtroom scene that climaxes the play, absolutely soar, capturing the simultaneous struggles between gullibility and skepticism, superstition and reason, the intellectual prison of religious dogma and common sense empiricism, personal revenge and public animus, as well as the plight of those falsely accused facing the inflexible state machinery.

Voorhees has wisely decided to include the moonlit encounter in the forest scene between Abigail (Jessica Neufeld) and John Proctor (Voorhees), a scene that is often omitted from productions of Miller’s play. Abigail, the teenaged girl who loves/lusts after small-homesteader Proctor and with whom she’s had an affair, has accused Proctor’s wife of the capital crime of witchcraft. Proctor gives Abigail a chance to admit that her accusations are false and that she has simply made up the claims of witchcraft, before he himself exposes them both as criminals. Extra-marital sex, “lechery,” was a crime punishable by imprisonment in puritan New England. This is an emotionally charged and complicated scene, Neufeld and Voorhees’ best; it examines the smoldering relationship that sparks the entire narrative. Why anyone would omit this scene is beyond me.

David Ross Paterson nearly steals the show as Deputy Governor Danforth. Patterson brings the heft of a classical actor to his portrait of a man intoxicated with embodying the power of the state, blinded by arrogance and vanity, consumed with exerting authority even if it means destroying the very community it is intended to govern and savoring his personal power over life and death. The contrast between Danforth’s archly superior and very British airs and the more common speech and demeanor of the locals boldly underscores the play’s theme of the potential horrors of a centralized authority as deluded by personality cult as the town’s hysterical collaborators.

The minor roles—and there are many in this cast of twenty-one—are played by some of L.A.’s finest actors, many of them members of the acclaimed Theater of NOTE ensemble (Lynn Odell, Lorraine Hill, Brad Light, Ashley Morey, Trevor Olsen, Michael Rhea, Rebecca Sigl, in addition to Ms. Neufeld), so many that this could be considered a Theatre of NOTE co-production.

Bernadette Speakes as Tituba (from the Elephant Theatre Company), Anthony Backman (from the Sacred Fools Company) who delivers a solid portrait of Rev. John Hale, the clergyman who eventually comes to his senses and Doug Burch’s Giles Corey also stand out.

While it takes time for Voorhees’s Proctor to find his footing in the early acts, by the end, in the big scenes for which this play is so justly celebrated, Voorhees excels, carrying us into that dark troubled place where the unjustly accused must choose between honorable conviction and expedient surrender to the overwhelming powers of state power run amok.

Follow the WSWS