The 59th Berlinale–Part 3

Intimations of changes to come—but nothing more

On the film series: After Winter Comes Spring—Films presaging the fall of the Berlin Wall

By Bernd Reinhardt

19 March 2009

Under the title Winter Adé—Vorboten der Wende, the German Kinemathek at this year's Berlinale showed a retrospective series of Eastern European films made between 1977 and 1989: dramas, documentaries, experimental films and animated films from the former Soviet Union, Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Romania. In this article we can only offer an overview and will limit ourselves to the German films. Most of these originate from the former German Democratic Republic (GDR).

These films illustrate the considerable estrangement between the official GDR establishment and the great majority of the population. The demands for "Perestroika" and "Glasnost," as the reforms were called in Gorbachev's Soviet Union, were supported by many artists in the GDR. In this sense, one can interpret these films as harbingers of the forthcoming dissolution of Soviet hegemony. The collapse of the GDR and the re-unification with Western Germany on capitalist terms, however, came as a complete surprise to these artists, most of whom opposed such a development.

Saturday, Sunday and Monday Morning by Hannes Schönemann (1979)

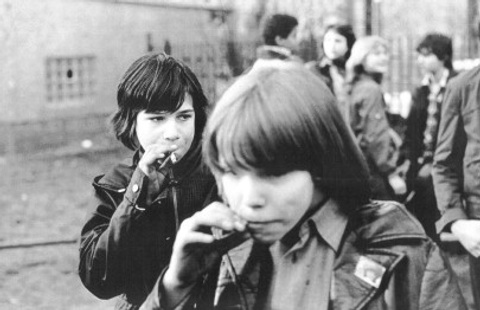

Why Make a Film About People Like Them? by Thomas Heise (1980)

These two student-made films stem from the time before the rise of Gorbachev, when troubles were already brewing in Poland. Schönemann's short documentation films members of an official youth organization during a weekend they spend in the country. The camera accompanies the apprentices, including prospective roofers and butchers, in the local pub, the disco, at home and at work. In the process, the young people talk about everyday things or have discussions, while the camera simply observes.

Saturday, Sunday and Monday Morning

Saturday, Sunday and Monday Morning

They resent the lack of leisure facilities. There is nowhere to play football and even the patch of grass they have used provisionally is now to be used to build a housing complex of bungalows. The aforementioned disco turns out to be only for the locals. People from outside the village are only allowed into the disco as a special exception—because of the lack of space, as the youngsters are told, while the camera is running. There are regular punch-ups between the youth fighting over the few females that are available. Most of the youth have already received sentences for assault. Only one of them is not a member of the official Stalinist youth organization, the FDJ (Free German Youth). But the others have joined merely to take advantage of the benefits of membership—for example, subsidized travel.

As in Jürgen Böttcher's 1965 feature film Born in ´45, which was never permitted to be released in the GDR, symbolic communication plays a central role. In a dictatorship like the GDR, it was important to write and read "between the lines." The camera follows its subjects as they go walking about, dancing, drive their mopeds, smoke cigarettes, shovel coal. In all of their actions there is an undeclared element of underlying resentment, their defiance and a striving to create their own free "space."

In a particularly striking scene, the youngsters are waiting on an empty village street for a railway bus. Some of the girls are dancing in the snow to the blurred, slightly grinding tone of cassette music.

Why Make a Film About People Like Them?

Why Make a Film About People Like Them?

In his film Why Make a Film About People Like Them? Thomas Heise takes a look at petty criminality amongst young workers in the Berlin district of Prenzlauer Berg. Sometimes in their homes, other times in the pubs, they talk openly about their many offences. And while some are arguing in front of the camera about whether two or three youth broke into the local shopping center in 1976, their mother is sitting right there with them. She knows, it was just her two sons. They talk about punch-ups at the "water-tower hang-out," about stealing motorbikes to joyride round the block. Even the kid whose bike was stolen says something. He says he won't report them. He himself comes from a problem family and thinks that strict state regulations are pointless. The brothers show their posters of their favorite bands. KISS is the most popular because after the show there is always a punch-up onstage and everyone joins in.

What is the point of making a film about these people?

Instead of debating how the conditions of these country kids could be improved, and what help these difficult youngsters and their overburdened parents really need, when the two films were shown at a GDR Film Festival, the presiding Stalinist officials just discussed the negative image of human nature that the films supposedly portray, saying that nobody should identify these as being true representations of the working class.

The existence of a whole layer of working class families whose criminality or alcohol problems were associated with generations of oppression, or who came to Germany as war refugees, like the mother of the two brothers—all of this is to be swept under the carpet. But Heise was emphasizing that these brothers were not simply petty criminals—they did heavy shift work at the NARVA Lightbulb Factory. Instead of helping such workers, the GDR bureaucracy labeled them anti-social and not suitable as subjects for "art." Both films soon disappeared from public view.

The aesthetic importance of these films lies in their lack of polish. They come across as raw, "uncut" and thereby very immediate—"cinema direct." There is no explanatory commentary. The camera tells the story—the filmmaker takes a back seat. The action is not manipulated, there is no attempt to prompt or influence discussion between the protagonists, or to provoke or setup situations, like in the French cinema verité, with its sociological tradition. Many GDR film makers were sick and tired of the Stalinist nit-picking, in which party bureaucrats criticized the admittedly "real" representations by saying they needed to show not what was "typical," but the higher, historical reality. The artists didn't want to resolve contradictions into a new "dialectical unity" (in practice concealing them, as was the practice in the official DEFA films), but they wanted to leave the contradictions open, simply show things as they really were, as they took place in front of the eyes—raw and uncut.

Both documentary films are well worth seeing, and can be compared to pages that have fallen out of a book. That also indicates the negative side of their method, of which Thomas Heise is still a typical exponent. His latest film in the Berlinale shows a two-hour juxtaposition of historical ruins (some of which are indeed very interesting) and is entitled as a result Material. It contains no attempt to show any overarching historical connections. History seems to have lost its significance, or, as Heise himself expresses it in his film, "History is a pile of stuff." The rejection of history inevitably leads into an artistic dead-end and lots of hastily juxtaposed "piles of stuff" have already found their home under the roof of post-modernism.

After Winter Comes Spring by Helke Misselwitz (1988)

To make this film, which was created under the strong influence of "glasnost" und "perestroika," the director traveled throughout the GDR in the second half of the 1980s to ask women about their life stories. She went to interview them in their workplaces or in their homes, or simply conducted the interviews while traveling by train from one station to another. The film prioritizes something that had always been treated as secondary to the "building of Socialism," namely, private life. The women talk very openly about children and men, about the difficulties of juggling work and family, and about their personal wishes and dreams.

After Winter Comes Spring

After Winter Comes Spring

One of the women is Christine, a shift worker in a brick factory. She is divorced and has an 18-year-old daughter with a slight mental handicap that leads her to behave aggressively. The latter uses insulting language while the camera is running. Christine describes how upsetting it is for her—she loves her daughter but at the same time has to keep her distance from her, otherwise she would just break down herself. She also suffers from the lack of understanding by other people in her social environment, who, instead of respecting what she has to cope with, exclude her from social activities because she has a daughter who is such a burden. She is practically seen as socially unfit. She had to work hard all her life since childhood, when she grew up with large farm animals and dreamed of being a professional horse-rider and traveling to other countries where she would learn about other cultures. This dream is one she will never be able to realize financially.

After Winter Comes Spring emphasises the world of emotions, the feelings of vulnerability and the personal yearnings which are universal experiences—although not everyone was seen as of equal worth in the GDR. Only on International Women's Day were there television news features about married life. Then GDR leader Erich Honecker would express thanks for women who stand by their husbands in industrial centres where the temperature is 20 degrees below freezing, and would pay his respects to female construction vehicle drivers. But even on Women's Day, the female underground train drivers in Berlin, whom the film producer visits in their driving cabins, have to work their normal shift as usual. The children's home director, a divorcee like nearly all the women in the film, speaks about the great responsibilities she shoulders for the children in the home, and how this leaves her with hardly any private life. But she says she will still fight hard to reach her personal life goals. "You only live once."

Particularly noteworthy is the poetic richness of this black and white film, which arose in an atmosphere in which trust and openness was being called for in the GDR. The entire film gleams and floats. Again and again the producer finds new images that illustrate what is soft, sensitive and dreamy, or show a gentle empathy in opposition to the harsh reality, whether through showing a hand working a monotonously stamping machine, or the hands of women who have to work all day handling dead fish.

The train journey is shown as being at the same time a journey along the tracks of people's lives. They cross other tracks, other lives, and at the end, many of them end abruptly at the banks of the ocean. We find ourselves on a railway ferry. From out of the sea rises a song, full of vigour and lust for life—"Summertime," wonderfully sung by Janis Joplin.

After Winter Comes Spring is like a breath of fresh air. "I wanted to give a platform to people who would normally never have a voice," said the female producer. It seems as if the women are saying "Look here, we are human too." And in the process, the Stalinist party machine (the SED) is hardly mentioned, because, as the film makes crystal clear, it is not the SED that kept life going in the GDR, but these women and their families, and they know it too. "Are we a royal kingdom?" asks the advertising worker ironically, as she relates her experiences at an awards ceremony where Berlin SED Chief Günter Schabowski paraded by with his entourage of officials, immediately drawing the attention from the award winners to himself.

At the 1988 International Documentary Film Festival in Leipzig, the film was received with a standing ovation and was awarded the Silver Dove. It was shown in public cinemas, and in discussions after the showings many members of the audience opened up about their own lives. In a sense, the gentleness of the film reflected and amplified the changes in mood brought about as a result of the ‘60s.

The time of creators of characters like "Balla," the unforgettable leading figure in the 1966 GDR film Spur der Steine (International English title The Trace of Stones; US English title Traces of Stones), who confidently threatens the party functionaries by saying he will "hang them out to dry" if they cause trouble—this time was over by the time the tanks rolled through Prague in 1968. The GDR film artists in the 1980s alternated between depression and naive but short-sighted hopes in the possibility of democratic reforms from above. According to the film producer herself, they were "going through changes in stagnancy."

The hardliners who dominated the GDR television media were not interested in broadcasting the film. They announced that it would never be shown on television. A year later, the GDR collapsed.

And what became of the film's protagonists? Some of them benefited from reunification. The former advertising agent set herself up as a self-employed yoga therapist. But the fate of the woman who was one of the shift workers, and was already leading a very hard life in the GDR, is tragic. After the closing of the brick factory in which Christine had worked so many long shifts, she had to take on a series of "one Euro jobs" and lives today on Harz IV (unemployment benefits). She has been unemployed for 12 years. Ninety percent of women in the GDR were in full-time employment, the audience is told by the film producer. They were consequently independent from men and gained a lot of self-confidence through their work and the feeling of playing a useful role and being needed in the workplace.

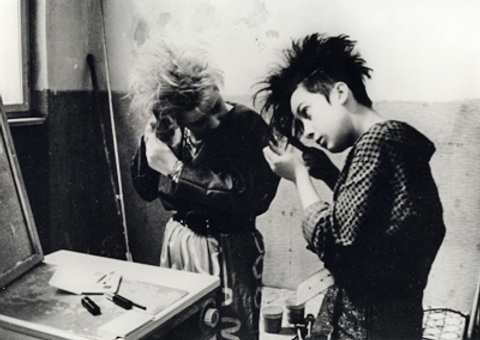

It's So Much Nicer Wherever We Are Not by Michael Klier (1989)

This film, produced by Michael Klier (born 1943), takes up a special position in the series. This harbinger of reunification takes place in the former West Germany, at that time seen as the heartland of the "class enemy." Klier's family fled as refugees from Czechoslovakia to East Germany at the end of the 1940s, and became GDR citizens in 1961.

It’s So Much Nicer Wherever We Are Not

It’s So Much Nicer Wherever We Are Not

Filmed in 1988, the film tells the story of some Polish youngsters who emigrate to America full of illusions in the "American Dream." On the way they stop over in West Berlin, where they work as exploited cheap labour in all imaginable "twilight zone" jobs, including prostitution. When they eventually get to their dream destination of New York, with the help of illegal bribery, they find that it is no different there than West Berlin or even Warsaw—the same sad, run-down streets, the same badly-paid jobs. Even the horrible neon lighting is the same.

One of the young Poles, Jerzy, comes across a musician in New York who used to play the accordion in his local pub in Warsaw. Now he is a street musician and pretends not to recognize Jerzy.

The black and white film, influenced by neo-realism, avoids all unnecessary dramatisation. Dialogue is restricted to what is strictly necessary. The story portrays life based on a tight economic formula: paying debts, earning money, taking on new debts. It shows the determination with which Jerzy pursues his goals, not only to get to New York, but also to find Eva, a young waitress from Warsaw, whom he met again in West Berlin working as a cleaning woman and prostitute.

The sober tone of the film is a refreshing change from the fashionable East European films that came later, with their brassy Balkan types and shady characters that expressed cinematically the overblown euphoria for European Union expansion into Eastern Europe.

For Klier, it is not about national outlooks, cultural diversity or the questionable attempt to show that, despite poverty, everyone can "make it." Completely without embellishment, he portrays a totally normal life in various cities in the world, where although people might speak different languages, their conditions are no different, whether they live in New York, in Warsaw or in Berlin.

It seems a bit over the top to treat this film as especially prescient about future events and to describe it as anticipating "in a casual but almost visionary way" the development of "the global migration movement" (Deutsche Kinemathek). The starting point of the film concept was not to overtly deal with the process of globalization that led to the collapse of the East European regimes, an event that Klier himself said took him by surprise.

Michael Klier was well acquainted with the giant flea market in Potsdamer Platz, the so-called Polish market, where in those days you could buy pretty much anything, from bric-à-brac to original Polish state carriages. As he said, "The dream of going west was at the heart of the spontaneous, collective mass movement. They all wanted to go west...." He shared this dream when he came to West Berlin shortly before his 18th birthday, his head full of American films, music and literature: he was fascinated by the energy that was unleashed by this dream, "...even when it turned out to be only an illusion."

The ironical title of the film, and its emphasis on the similarity of misery in Warsaw, West Berlin and New York, leads to the conclusion: if that is the case, you might as well stay at home. Even if the producer himself had the privilege to live in what was obviously a far more genuinely international way than was available to the citizens of the GDR with the abstract "internationalism" of the SED, it is still true that Klier's film offers more insight in terms of "Presaging the Fall of the Wall" than the official GDR films.

On both sides of the wall, however, nothing in these films represented more than a vague intimation of what was to come.

Follow the WSWS